The Old Station House1 at Tha Ta Fang2

In March 1944, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) attempted an invasion of Imphal and Kohima in India. By July, it had been driven back into Burma, suffering its worst defeat to that point in the war.3 In the months after, the retreat back into Burma evolved into a rout. Numbers of IJA troops pushed south towards Rangoon. A significant number of them turned east towards the land of Japan’s ally, Thailand. And most of those were funneled into the Thai border district of Khun Yuam.

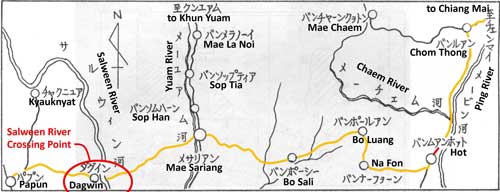

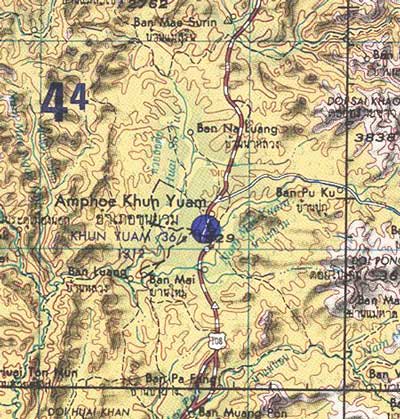

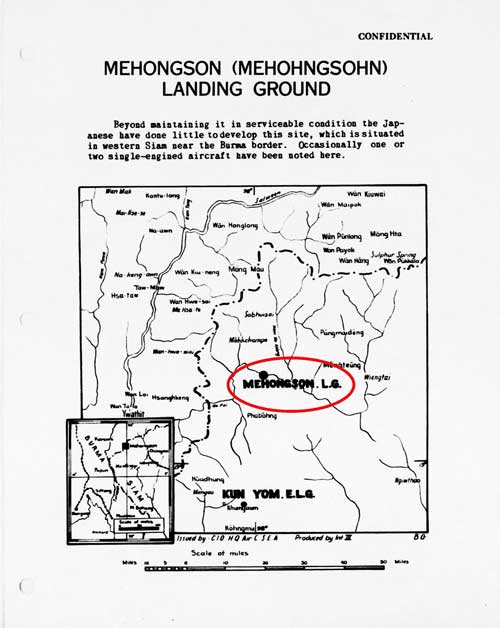

However, numerous local cross-border trails existed, as well as long-established trade routes, with connections to points other than Khun Yuam. One of those used by retreating IJA troops tied Papun in Burma to Chiang Mai in Thailand:4

It crossed the Salween River as shown at Dagwin on the Burma side with Tha Ta Fang (not here labeled) facing it in Thailand.

On the Thai side, overlooking the trail where it crossed the Salween River at that time was this structure which still stands today:((Extract from IMG_20130310_153628.jpg, 10 Mar 2013. Annotation by author using Microsoft Publisher.))

Up close, it looks like this:5

Most likely, IJA troops following this trail saw the building, and some may have stopped to overnight in it, though it would have been an exhausting climb for most who were starving, wounded, or suffering from malaria — or, often, afflicted with all three. Thai Police manned the station during the war. There is no evidence to suggest that the IJA assigned personnel there. Since the border at that time ran between friendlies — Japan-occupied Burma and its ally, Thailand, there was no justification for allocating IJA troops there during the war.

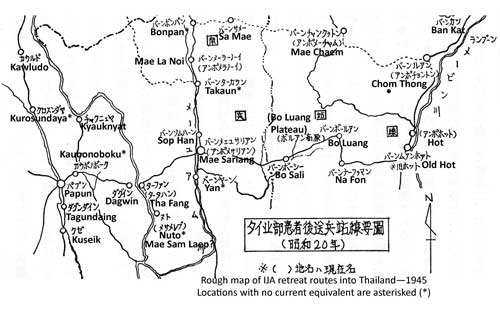

Nonetheless, the building is today called the “Japanese” building / fort / station by tour boat operators, perhaps recalling Japanese war veterans who passed through the area in the late 1970s looking for remains of IJA troops. Guides may justify the name by saying that the IJA built the structure during the war. Those veterans passing through here 40+ years ago were probably ferried by the fathers of the current boat pilots. The veterans made a sketch of their access to the area:6

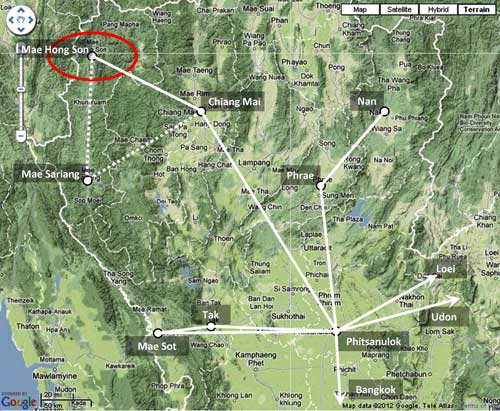

Their approach to the site, via the Saween River from Mae Sam Laep, is the same as that most often used by tourists today. The veterans, however, were concentrating on recovering remains of IJA troops who were rumored to have been buried in the area. Their journal mentions Tha Ta Fang’s police post and recalls that it was there during the war.7

The building was actually erected in 1901, financed by locals who were trying to encourage the Thai government to protect them from Burmese bandits. It is not known if contributors included the great logging companies working in the area at that time. If so, that would be evidence of the lawlessness of the times in that area. The station was manned continuously from its construction in 1901 through to 1981, when the office was moved to a new building, closer to the town.8

A current view of the front of the old station:9

The structure is quite similar to the police station in Mahaphon Subdistrict of Mae Taeng, as photographed in 1927 by M Tanaka:10

Some comments about the Mahaphon photo help explain the station building at Tha Ta Fang:

. . . the police station was built as a two-story fortress so as to repel marauding criminals. The four sides of the ground floor are entirely covered with wooden boards which have gun ports. From the front, there is only one narrow set of stairs so that only one man can up or down at a time. The police officer on the upstairs is able to see whether the suspect carries a weapon or not. There are holes on second ground floor for the light coming through the downstairs – not completely dark. The ground floor is also used as a supply storage of foods and weapons.11

At the Tha Ta Fang structure, the staircase is wider — enough to accommodate two people. There are no holes in the second floor to allow lighting of the first floor. However, gun ports penetrate the walls in profusion on both floors. While the wall thickness for the Mahaphon station is not recorded, that for Tha Ta Fang is about 14 cm (5 1/2 inches):12

The buildings testify to the needs of a different time, for security against armed attack not experienced today in Thailand. Wikipedia‘s discussion of a blockhouse helps explain:

In military science, a blockhouse is a small, isolated fort in the form of a single building. It serves as a defensive strong point against any enemy that does not possess . . . artillery. . . . [They] were constructed for defence in frontier areas . . . [and were once] commonly made from very heavy timbers . . .

Blockhouses [now of concrete] have become a feature of the conflict in Afghanistan, being used as strong points to control the contested Southern provinces. . . .

While a newspaper article observes deterioration of the wood in the Tha Ta Fang structure,13 it is still remarkably sound after 110+ years. The lack of initials carved in the wood suggests that the teak is still very hard. And that teak continues to prosper despite severe deterioration of the metal roof and resulting exposure to the weather.

The building is well-known locally and is a favorite of a recent Mae Sariang Boriphat Suksa public school14 teacher, Seksan Lakbun15, who is interested in the history of the area. His enthusiasm led to the school maintaining a small museum on local history, and that museum is listed as one of the “things to see” in the town. In addition, the teacher succeeded in getting the Thai government to place the building on a national register of historical sites. Finally, he got the building added to a government projects list for restoration.13

The teacher’s dynamism apparently led to his being promoted to head the school in Tha Ta Fang, very close to the old station building, but unfortunately too far from the local political power structure: his former school closed his museum after he left, no one in the National Museum at Chiang Mai now knows of the site, and funds to restore the building have apparently been transferred to other projects.16

Regardless, a current teacher at the school, Surachai Tipkam, who knows Seksan Lakbun and is familiar with the old Tha Ta Fang station, proved hospitable and knowledgeable, and welcomed our curiosity: he used his smartphone to give us Internet links for more information about it. Prime websites proved to be:

1 Youtuber:Kraisak Yongpetch17

2 The OK Nation Blog: The OK Nation Blog18

APPENDIX

Additional relevant maps

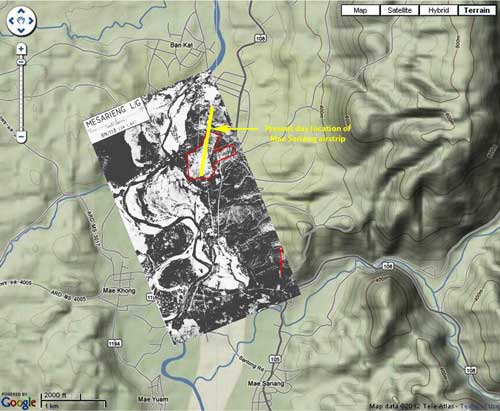

An oblique view by Google Earth looking north at the site emphasizes its relative isolation:19

Map by IJA Veterans of WWII routes in Northern Thailand: extract covers generally the same area as the first map above, but in more detail:20

Additional photos

A view from the side which tends to emphasize the ‘blockhouse’ aspect of the structure:21

Additional text

Account of IJA Veterans searching the Tha Ta Fang area for remains of WWII casualties.22

The Riverbank Team, including Area Commander Ashina, Group Leader Yoshino and Member Kanda, moved out. There may have been a separate interest in going to the border which was formed by the Salween at this point; and it can also be judged as an extra “benefit” [an improved probability of finding remains]. But that line of thought did not enter into the decision to go to the Salween. Early next morning, the Riverbank Team jeeped down the riverbed road. In three hours, they reached Mae Sam Laep on the Salween. The investigation division had only investigated this one spot on the Salween.

Group Leader Yoshino recorded:

From here, forty minutes upstream in a boat with an outboard motor, and we were in Ban [Tha] Ta Fang. On the opposite bank is Dagwin, Burma. Traveling on to Papun would have taken about more one day. In Ban [Tha] Ta Fang there is a police sub-station, just as there was during the war. Three households with 24 people currently reside there. Our main guide had to be hospitalized for malaria in a hospital on the Burma side of the Salween. Unfortunately, only he knew where the two graves were. From here, 2 km west of the village of Ban Chou , a mountain tribe village of 15 households, it was a two day journey to Chiang Mai and there are no villages in between. It was said by residents in Ban Chou Village that there was a grave site 15 km away. It wasn’t practical to follow that up, so, facing the direction of that location, we pressed our hands together in memory of those who might be out there, and abandoned Ban [Tha] Ta Fang. Because of the poor condition of the truck, we overnighted in Mae Sam Laep.

Rough translation of Daily News article about the Tha Ta Fang Station23

Tha Ta Fang’s 111-year-old wooden border station may be restored as a tourist attraction. Already registered as a historic site, efforts will be required to maintain it for future generations to enjoy. It functioned as a police station on the Thai-Burma border, keeping the Salween River secure. Tourists already frequent the site on a regular basis.

. . . Located on a cliff along the Salween River . . . registered as a historic site by the Office of the National Museum of Archaeology . . . .

During WWII, the station chief was a sergeant. . . .

The building is constructed of heavy wood, which is deteriorating. . . .

The sides of the station had gun ports on both floors. In 1981, the police office was moved from the old station building to a new building at Tha Ta Fang. . . .

The building has played a significant role in Thailand’s history and should be preserved. . . .

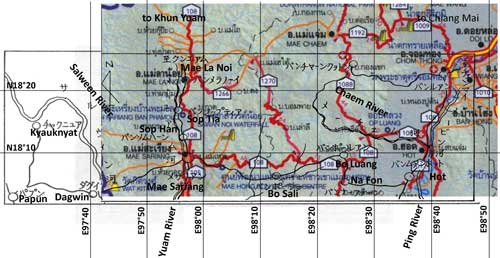

Derivation of current place names from those in katakana on IJA Veterans’ maps

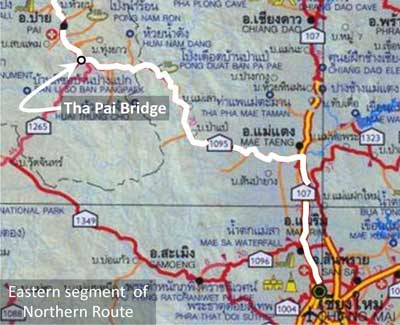

Certain place names in katakana on IJA Veterans’ sketch maps are difficult to correlate with place names on current maps. The veterans apparently used maps from WWII and those current in the 1970s to assemble the sketch maps used in their search for remains; but in addition they did not hesitate to grab place names as used ‘on the ground’ by locals in an attempt to better locate certain points. To assist in correlating those names rendered in Japanese with current location names, a veterans’ map was overlaid on a current national highway map of the area:24

The map sketch was intended only to provide general details, so it has no scale, nor even a consistent scale across the whole drawing. As a result, it was stretched to partially fit the scale map (in color) beneath.

Results, proceeding from left:

チヤクニユア (CHIYAKUNIYUA) [current place name determined from approximate location on the west bank of the Salween] KYAUKNYAT N18°15.35 E97°30.27

ダグイン (DAGUIN)

DAGWIN N18°04.12 E97°40.92

バンツプテイア (Ban TSUPUTEIA)

SOP TIA N18°17.73 E97°54.73 (aka for Mae Tia . . .)

バンソムハーン (Ban SOMUHAN)

SOP HAN N18°12.37 E97°55.70

バンボーシー (Ban BO SHI) [tambon in Amphur Hot] BO SALI N18°06.07 E98°13.67

バンナーフヲーン (Ban NA FUON)

BAN NA FON N18°06.0 E98°22.0

バンチヤーソクヲトン (Ban CHIYA SOKUOTON) [the map locates the place on the Chaem River at a road leading to ‘Ban Luang’, aka Chom Thong; that junction would point to the Mae Chaem area. Only a very rough approximation of the katakana was found in the Mae Chaem area. This conclusion is generally confirmed by another map in the veterans’ book, p 421.] MAE CHAEM N18°29.83 E98°22.27

バンポールアン (Ban PO RUAN)

BAN BO LUANG N18°09.03 E98°21.30

バンルアン (Ban RUAN) [Ban LUANG: a tambon in Amphur Chom Thong] CHOM THONG N18°25.60 E98°40.68

| First published on Internet | ||

Last Updated on 29 February 2024

- The battle was recently covered in great detail in Edwards, Leslie, Kohima: The Furthest Battle (Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2009). [↩]

- Sometimes as only two words: Ta Fang or Tha Fang. N18°04.168 E97°40.954 Source: Garmin GPS 12. [↩]

- The title refers to the building’s function as a ‘police station’. Technically, the structure might better be referred to as a ‘blockhouse‘. [↩]

- Map is derived from 戦没者遺骨収集の記録 ピルマ・インド・タイ [Journal on Collection of War Dead: Burma, India, Thailand] (Tokyo: All Burma Comrades Organization, 1980), [hereafter Journal on War Dead], p 454; annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. Derivation of location names in English from the Japanese katakana is explained in the Appendix to this article. Transliteration by Yoshio Fukuda. [↩]

- IMG_20130310_152214.jpg, 10 Mar 2013. [↩]

- Journal on War Dead, p 458. Annotations in English by author using Microsoft Publisher. [↩]

- Journal on War Dead, p 458. [↩]

- ฝั่งริมฝั่งลำน้ำสาละวินอายุ 111 ปี เป็นแหล่งท่องเที่ยว “แม่ฮ่องสอน”, เดลินิวล์, “Aimed at restoring the 111 year old station on the banks of the Salween river as a tourist attraction, Daily News, 20 Nov 2012″, [↩]

- Photo by Peter Herrett: IMG_3130a.jpg, 07 Jan 2011. I thank Peter for bringing the structure with its history (as alleged by boat operators) to my attention. [↩]

- Photo taken by M Tanaka. Photo from Payap University Collection of Photos donated by Boonserm Satrabhaya. Detailed description from Payap University website. Proper location of the photo’s subject from caption on copy of the photo hanging in the Gymkhana Club, Chiang Mai. Date of photo from Satrabhaya, Boonserm, Lanna–mua tawa (Yesteryear in Lanna) (Chiang Mai: Bookworm, 2007) [Thai lang] สาตราภัย, บุญเสิม, ลัานนา . . . เมื่อตะวา (เชียงใหม่: ผลิตและจัดจำหน่ายโดย, 2007), p 176. The Mahaphong station was only recently replaced by today’s standard concrete ubiquity. [↩]

- Description translated from Thai on the Payap University website. That website has apparently discontinued an online presentation of the university’s collection of historical photos: thus the reference to the description cannot be linked. Translation by Tip Boonrang. [↩]

- Photos IMG_20130310_150627.jpg, IMG_20130310_150545.jpg, both 10 Mar 2013. In the photo on the right, a Garmin GPS12 has been placed atop the wall to gauge its width. The GPS is 14.9 cm long, almost six inches. The wall thickness is a bit less than that. [↩]

- Daily News, ibid. [↩] [↩]

- โรงเรียน แม่สะดรียง บริพัตรึกษา [↩]

- เสกสรรค์ หลักบุญ, now at Tha Ta Fang School (โรงเรียน ท่าตาฝั่ง). [↩]

- The last per Surachai Tipkam, a teacher currently at the school. [↩]

- The Old Tha Ta Fang Station (a video) by Kraisak Yongpetch. [↩]

- A blog run by the teacher now located at Tha Ta Fang School: Seksan Lakbun. [↩]

- Google Earth, accessed 22 Apr 2013. Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. [↩]

- Journal on War Dead, p 421. Transliteration by Yoshio Fukuda. [↩]

- IMG_20130310_152107, 10 Mar 2013. Front of the building is to the right. [↩]

- Journal on War Dead, p 458. Translation by Josh Skiles. [↩]

- Daily News, ibid. Translation by google translate. [↩]

-

This map was made by superimposing the first map on the previous page on an extract from แผนที่ทางหลวงประเทสไทย Scale: 1:1,600,000 (กรุงเทพมหานคร:กรมทางหลวง, 2009) [Road Map of Thailand, Scale 1:1,600,000 (Bangkok: Department of Public Highways, 2009)] (folded map).

It should be noted that listeners with ears tuned to Japanese or English languages “hear” Thai words completely differently from each other — as well as completely differently from what Thais hear. And neither English nor Japanese language alphabets are designed for accurately recording Thai language sounds. So, when those foreign listeners transliterate what they think they hear into what they believe is a proper rendering in Japanese and English written text, the end results can be very different; and extremely difficult to correlate.

The problem is made more difficult because different Thai individuals from within a relatively close distance of a particular place may either pronounce its name quite differently or actually use different names to identify that same place.

Further, some place names used locally are simply not recorded on maps.

Finally, all Royal Thai Survey Maps carry the warning, “There are numerous identically named villages portrayed on this map”. And that warning applies equally to place names on different maps. [↩]