Summary

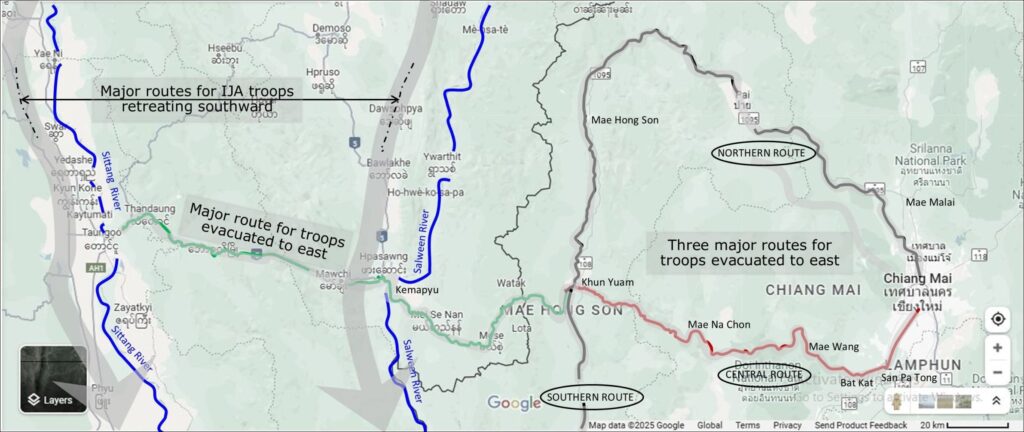

Following Japan’s disastrous defeat in its attempt to invade India in the first half of 1944, numbers of its troops eventually retreated south along the Sittang and Salween Rivers towards Rangoon. On that way, the troops crossed a road heading east out of Toungoo1 (Google Map link) towards Khun Yuam (Google Map link) and the relative sanctuary of Thailand. Khun Yuam had apparently become well-known for its having been the westerly objective in Thailand for the IJA 15th Division road construction connecting from Chiang Mai prior to the invasion. On encountering the road at this later date, unit commanders directed troops disabled by wounds, injuries, disease, and malnutrition to detour to Khun Yuam.

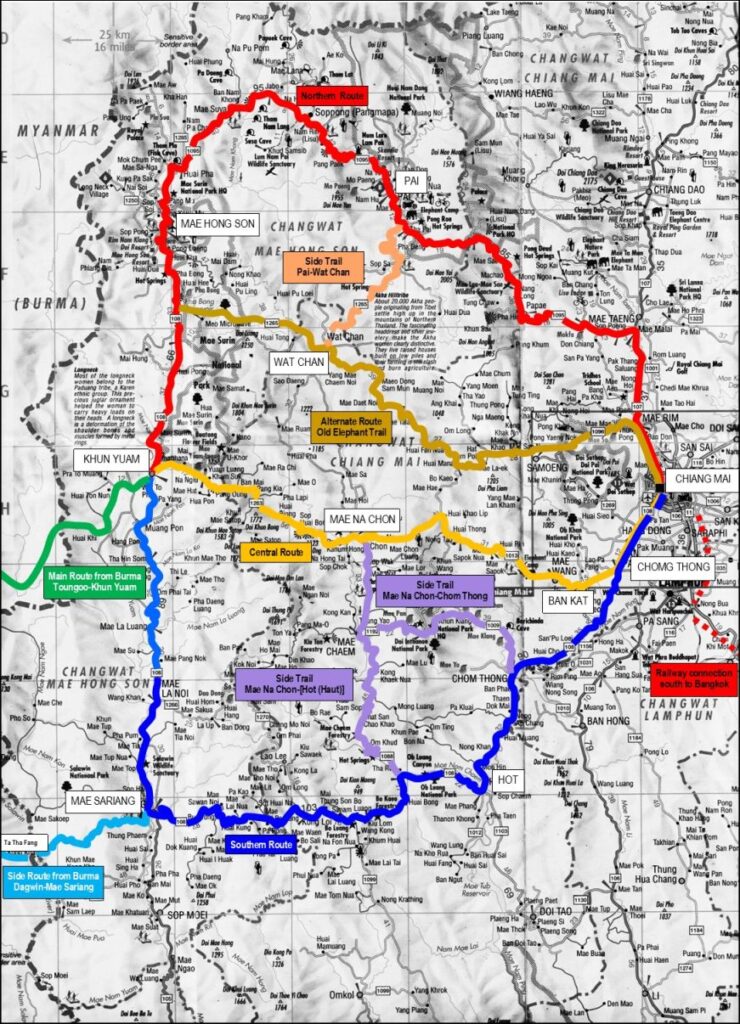

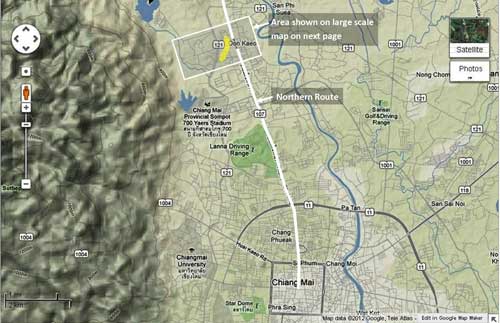

At Khun Yuam, three major routes developed for reaching Chiang Mai and its medical services:

● Northern through Mae Hong Son (Google Map link) and Pai (Google Map link)

● Central through Mae Wang (Google Map link) and Ban Kat2 (Google Map link)

● Southern through Mae Sariang (Google Map link) and Hot (Google Map link)

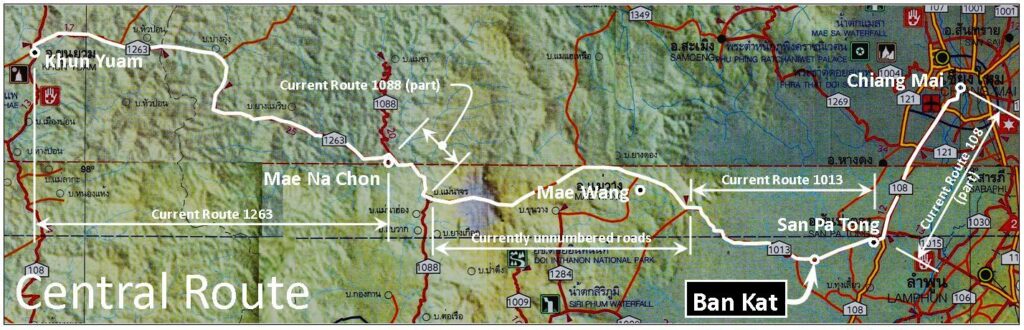

These pages will focus on the Central Route (traced in white above), and particularly Ban Kat near its eastern end.3 Traveling east, the Central Route eventually went thru Ban Kat, site of the only temporary IJA clinic on that route before reaching Chiang Mai.4 Years later, the largest monument to the IJA in the north of Thailand would be established in Ban Kat.

Background

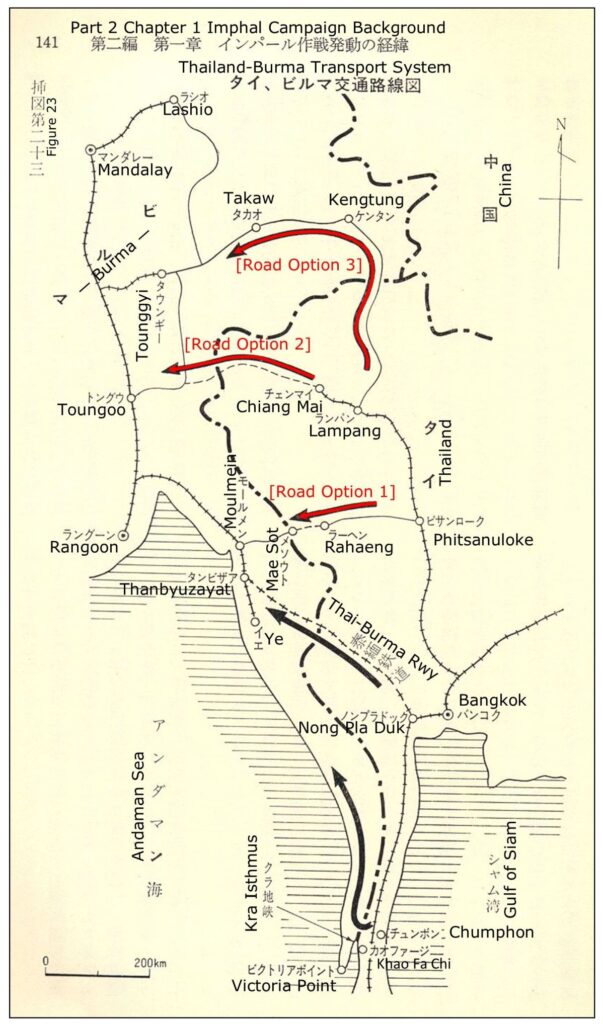

Even early in the war, Allied submarines had been seriously impacting Japanese shipping on which IJA forces in Southeast Asia were effectively totally dependent. The Japanese command realized that it needed to minimize exposure of that water-borne supply chain to Allied attack: hence the construction of the Thai-Burma “Death” Railway and the Kra Railway which reduced the 3400 km circumnavigation of the Malay Peninsula by 2600 km to Bangkok and perhaps 1100 km to Rangoon (a lesser savings because after crossing the Kra Isthmus by rail, the cargo was generally reloaded on small coastal freighters which continued north, hugging the west coast of the peninsula.5 With the adoption of IJA plans to invade India, the Japanese command felt the need to develop an additional support road connecting the Northern Line of the Thai Railway (Bangkok-to-Chiang Mai) to the Burma transport system. Three routes were considered, shown with red arrows in the sketch below. “Road Option 2”, the middle route (traced simplistically below by Japan’s official military history), was ultimately chosen because it used the most northern terminus of the Thai Northern Railway Line, at Chiang Mai, and was to connect to the road-rail-water transport hub in Toungoo, for a distance of 645 km (For more about the choice, see Tanaka in 1930).6

From Chiang Mai the road was to arch north, then west, then south, roughly following what is now, generally, Thai Interprovince Highway 1095, to Khun Yuam, and then head west to meet a British-built road at the border and continue to Toungoo (the connection to Toungoo seems to have already existed since Japanese plans did not assign any unit to improve it.7 The route was to look something like this:8

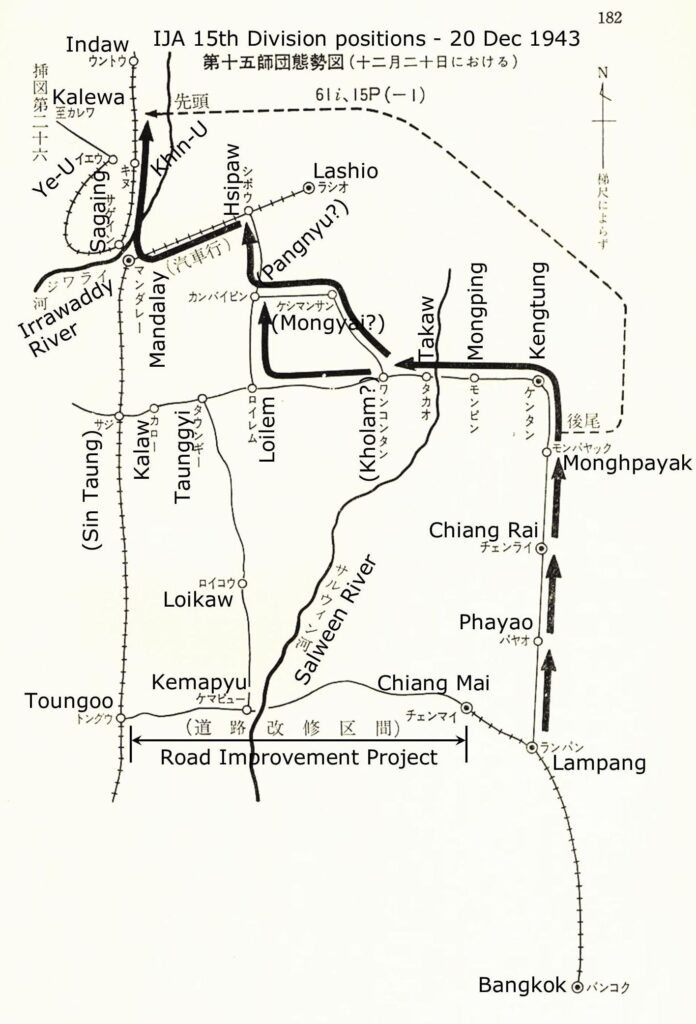

But the schedule for implementing Road Option 2 proved impossible to meet (and the routing had perhaps been misguided to begin with). As a result, the 15th Division which had been assigned to build the road as its own avenue to Toungoo ultimately had to backtrack from Chiang Mai to Lampang. There it followed the earlier rejected Road Option 3 north on poor, but long existing, roads to Kengtung and points west. Schematically, again from Japan’s military history:9

However, some 15th Division personnel remained in Thailand to continue construction of the planned road. Ironically it was completed in time for the use of those troops defeated in India who were retreating south along the Sittang and Salween (now Thanlyin) Rivers. In that retreat, they crossed the road running east from Toungoo to Khun Yuam in Thailand (shown below in green):10

At those junctures, troops judged seriously injured in combat or ill, particularly with malaria, were diverted east towards the relative sanctuary of Thailand. Aside from Allied air attacks, some of the natural obstacles encountered by the retreating IJA troops on the western part of the road, from Toungoo to Kemapyu, are described in a 1948 Burma road guide.11 Relevant text:

[p 1] The late war has brought many changes to Burma, and not the least amongst these has been the change in Burma’s roads. For four years little or no maintenance was carried out, roads, previously good, fell into disrepair, bridges were bombed and destroyed . . . .

[p 81] . . . Toungoo—Mawchi Mill Camp (98 miles)—

This road, which is a private road, represents a great engineering feat. It was opened for traffic in 1937 and has meant a great saving in distance to the Mawchi Mines (Google Maps link) . . .[end p 81]

[p 82]. . . The 13 miles from Toungoo to Pathichaung [~Thandaung] is more or less flat. At Pathichaung the Mawchi road forks right from the Toungoo-Thandaung road . . . .

[p 83] The chief difficulty about the road is its exceedingly twisty nature and its narrowness. One way traffic is therefore necessary . . . Where cars are met on a one-way section, it is generally possible to pass after certain amount of reversing, but great care in, driving is required.

At about MS 23 the road follows the Thaukyegat Chaung up to M.S. 25/3 . . . The chaung is crossed by a Bailey bridge12 at Paletwa and in the next 20 miles climbs to 3,500 feet at Thawso . . . . After a descent, the road rises to 4,500 feet at the Burma-Shan States Boundary (about MS 67) (Google Maps link). After a short descent the road again rises to 4,500 feet before beginning the final descent to the Mawchi Mill Camp (2,000 feet). . . . [end p 83]

[p 85] Mawchi一At MS 96 the road straight on leads to Mill Camp (MS 98) and connects here with the PWD Road to Kemapyu—Loikaw. The fork to the left at MS 96 leads up to the Mawchi Mines Offices at Mine Camp, a distance of about two miles, . . .

From Myanmar Mines13 (Myanmar Government link no longer active):

[Mawchi Mines] situated in the southwestern part of the Kayah State, was the largest tin-tungsten mine in Burma before World War II [Wikipedia states, “In the 1930s, the Mawchi Mine was the world’s most important source of tungsten. Mawchi contained the world’s largest granite-hosted tin-tungsten vein system before World War II.”(Wikipedia, Mawchi) (offsite link)] . . . . In 1938 the mine produced 4646 tons of mixed tin-tungsten concentrates which was about one-third of the total tin-tungsten production of Burma.

From the Melbourne Argus Week-End Magazine, 13 Oct 1945,14 “The Road Over Which the Japanese Tried to Escape Into Siam is Picturesque and Populous,” by S. Crozier:

FOR 98 TORTUOUS MILES [155 km] the road twists and climbs through the Shan Hills from Toungoo to Mawchi. As the crow — or the aeroplane — flies, the distance is only about 45 miles due east, but the road must follow the mountain contours, falling into valleys and doubling back on to its tracks.

WHEN THE ARRIVAL of the Japanese was imminent the road was mined in several places, and its two bridges destroyed. In view of the practical impossibility of by-passing the-road in any way-with a jungle covered mountain face on one side and a steep drop on the other it was estimated that these measures would hold up the Japanese for at least a fortnight; but in actual fact they had lorries through in five days.

Mawchi is in the Southern Shan state of Karenni. . . . When the Japanese were endeavouring to escape from Burma into Siam they made for this border, but they had to contend not only with Allied attacks and with the treacherous terrain, but also with the guerrilla harrying of the Karens themselves.

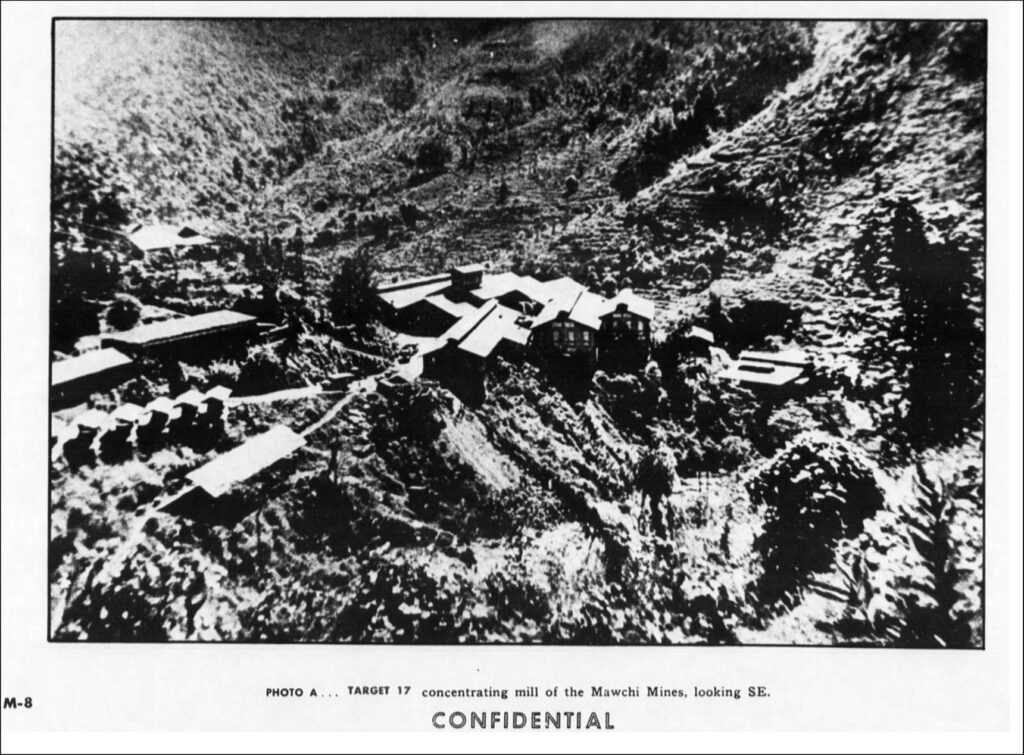

From an Allied intelligence report on targets in Burma, for which the mine was ranked number 17:15

. . . and [descends] again for a similar distance where it meets the Main Road to Mill Camp and Kemapyu. This hill section requires extra care in driving.

Mawchi—Loikaw (92 miles)—The road descends rapidly into Kemapyu (MS 15 from Mawchi) ))

For IJA troops arriving at Khun Yuam (except for one connection to Mae Sariang), three primary choices developed regarding how to continue — the objective being Chiang Mai. The three, with a few of the numerous impromptu secondary roads and trails which also developed are shown below:16

Northern, in red (future Thai Roads: part 108, 1095, and 107; 292 km)

Central, in yellow (future Thai Roads 1296, 1088, 1013, and 108; 212 km)

Southern, in blue (future Thai Roads 108 (south, then east, then north; 309 km)

The northern route, though not the shortest, was judged the least taxing of the alternatives. While the first 173 km section from Khun Yuam to Pai had to be covered on foot, for the section from Pai on to Chiang Mai, motor transport was available with some clinic services at Mae Malai. Thus it became the route of choice for those most ailing.

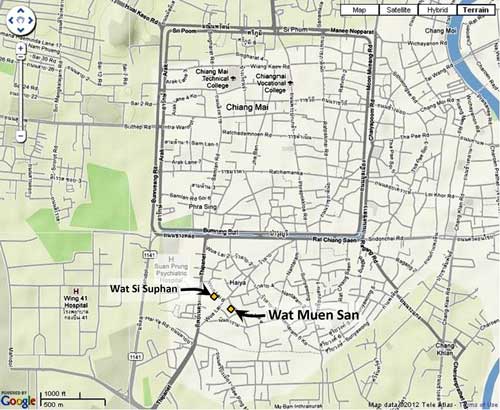

That was in contrast with what became known as the “Central Route” as shown in the map at the top of the page. The 160 km from Khun Yuam to Ban Kat had to be covered on foot and crossed some very challenging terrain, which included the declining but still rugged backbone of Thailand’s highest peak, Doi Inthanon. Limited medical facilities were available at Ban Kat and, a few kilometers to the east, vehicles could pick up personnel for the trip to Chiang Mai. IJA personnel typically took 22 days to traverse the 160 km to Ban Kat. Wat Muen San in Chiang Mai was perhaps another 30 km beyond17

_____

Chronology relevant to the IJA presence in Ban Kat and the subsequent monument erected there actually starts in the 1890s.

1890s: Teacher-monk Zaotamutein established Wat San Khayom18 in an area just north of present day Ban Kat; the site included a water well.19

1913: At Zaotamutein’s death, the wat and its well were abandoned.20

1913-1941: Following abandonment of the wat, Thai highway bandits who robbed and killed travelers, primarily on the Hot to Chiang Mai Road, dumped their victims’ bodies down the abandoned well at the old Wat San Khayom. In addition, the well became a favorite dump site for bodies resulting from local drug wars (which existed even back then); nationalities in this activity came to include not only Thais, but also Burmese and Jin Haw Chinese. Over time, the number of bodies accumulated; this, coupled with no maintenance, eventually filled the well in above the water table and it was judged dry.21

1941-1945: There are three primary sources for information about activities at Ban Kat during the period when the IJA was present.

There are three primary sources for information about activities at Ban Kat during the period when the IJA was present.

It must be noted that access to all three was only possible through the gracious assistance and guidance of Konishi Makoto, manager of the Japanese War Memorial at Ban Kat.22

SOURCE 1. Two sisters, Komloo and Yai Yin,23 lifelong residents of Ban Kat, at ages 15 and 18, were present when portions of the IJA, defeated at Imphal and Kohima, India, retreated via the “Central Route” which goes through the town.24 With parents emigrated from Burma, the sisters’ first language had been Burmese which was later supplanted by Tai Yai. They grew up in a house on a lot along Bat Kat Soi 4/625 which is now occupied by Komloo’s house and shop.26

Sisters Kamloo & Yai Yin, with able interpreter, Wiyada ‘Noi’ Kantarod, at Wat Chamlong where they were interviewed.27

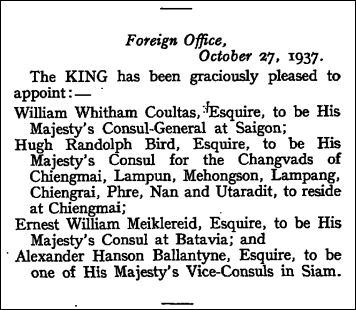

A significant number of Ban Kat residents at that time were relocated Burmese. They congregated in the south of the town. The two active wats in that part of town, Chamlong and Umpharam, were manned by Burmese monks. Another wat — long abandoned — was Wat Maan, or Wat Muan To near the center of the town; the latter means “Burmese wat” in Burmese. The sisters maintain that a British administrative type was present in the village before the war to oversee interests of the Burmese there. They believed him to be a representative of the British colonial government in Burma; however, he would more likely have been an employee of one of the British logging companies.28

In 1945, the sisters sold vegetables and noodles to Japanese soldiers at the local market which was located at the east end of their soi.29 Soldiers used rice30 and salt to barter for market goods; they did not have any medicines to trade (as some had been able to do in Khun Yuam). The soldiers would combine everything they bought in large kettles, cook it up, and then dole it out with rice container lids.

There was a lamyai plantation where the local market is today, directly across the street from Komloo’s house. At that time, the street was just a dirt path.

The general alignment of the main road serving Ban Kat, with connections immediately east and west, was the base for Thai Route 1013 today.

The first time Yai Yin saw any Japanese was in 1945 when soldiers were returning from Burma. Neither sister recalls any Japanese ever having passed through the town previously: such might have occurred in mid-194331 if an IJA scouting crew had passed through, evaluating the suitability of the road through the town for supporting the Japanese invasion of India.

From Khun Yuam (see map at top of page), 99 km west of Ban Kat,32 a few high-ranking officers rode in on horses;33 but most soldiers walked. No one came by motor vehicle: “roads” were, in most instances, nothing more than paths. Vehicle fuel was simply not available between Kemapyu in Burma and Ban Kat: some vehicles by virtue of fuel siphoned from stalled vehicles managed to get as far as the Khun Yuam area.34 For transport just in the Khun Yuam vicinity, some vehicles had been converted to steam, fueled by wood or coal.35

Satellite view of Ban Kat area36 (circled numbers refer to text following the map):

From Khun Yuam, Japanese soldiers arriving at Ban Kat would have last passed through Mae Na Chon (west of Map Point 1 directly above)37 There was no mention of self-powered vehicles operating in Ban Kat. This was the result of the path to Chiang Mai crossing the Nam Mae Khan (the Khan stream), at Map Point 7, about three kilometers east of Ban Kat: the unbridged stream was an effective barrier to motor vehicles.

Coming into Ban Kat (Map Point 2), soldiers were to report to Wat Maan38 (Google Maps link) for medical evaluation and then assignment to quarters.

The ruins of Wat Maan (Map Point 3) were visible during our visit in 2008 through the heavy foliage:

More recently, vegetation obscuring the building has been cut back revealing its true extent and more likely appearance 80 years ago:

Because of their large numbers, however, control was difficult and some soldiers never “reported in”, but just wandered into the various living facilities. Soldiers stayed not only at the wats, but also in innumerable tents scattered throughout the Ban Kat area. Some troops were sent 1.6 km north to the ruins of Wat San Khayom,43 (Google Maps link) though the ruins themselves would have provided no shelter:

More typically, soldiers wandering into Ban Kat went past Wat Maan and Komloo’s house/store, Map Point 4,26 and turned south to Wats Chamlong (Google Maps link) Map Point 5,45 and Umphara (Google Maps link), Map Point 6,46 to overnight.

Both Wat Chamlong and Wat Umpharam survive and prosper today:

Wat Chamlong47 Wat Umpharam48

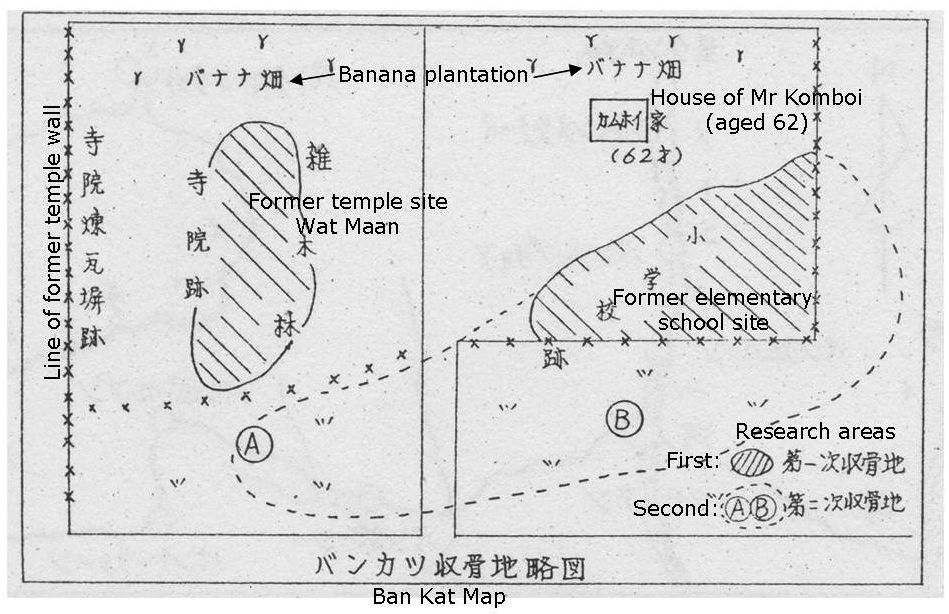

There were no civilian medical facilities in Ban Kat, and apparently only a very rudimentary clinic set up by the IJA at the ruin of Wat Maan: Soldiers who died around Ban Kat were buried on the grounds of Wat Maan; which extended to include the current residence of a Mr Kamboi. See map sketch below:

Very little is known about Wat Maan, earlier rendered as Wat Muai To,50 other than the name means ‘Burma’ in both the Tai Yai and Burmese languages; this refers to the nationality of the monks who established it. Superstitious local residents avoid the area for all the potential spirits that might reside there. Mr Komboi is apparently not superstitious.

Because a stream, the Mae Nam Khan, cut across the road to Chiang Mai about three kilometers east out of the town, motor vehicle transport only began from that point51 on to Chiang Mai with its better medical facilities.

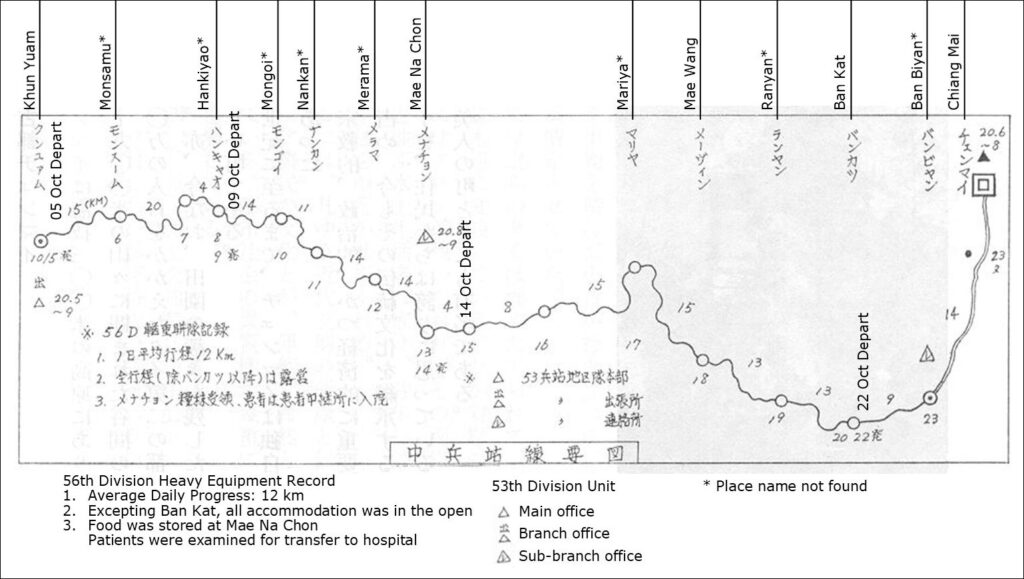

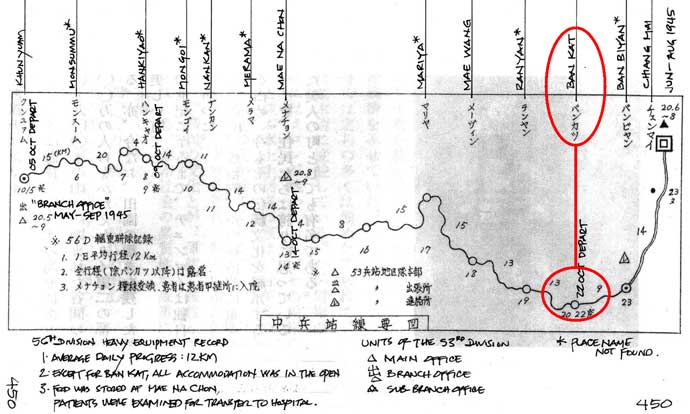

SOURCE 2. Japanese war veterans organized an effort to recover IJA remains in Thailand, Burma, and India which got underway in 1977. The highlights of their efforts were published,52 but there is little information about conditions at Ban Kat. It was located on the Central Route, for which the following map was provided:53

What was presented were these observations:

Patients / walking wounded were sent via the northern route because it was believed to have fewer steep slopes and there was a greater number of way point stations than the very mountainous (but shorter) central route. . . . For those in fairly good physical condition, the central route was a reasonable alternative . . . .54

Those IJA troops following the Central Route first passed through Mae Na Chon, where the village chief during the war recalled these details which were generally relevant to Ban Kat, 68 kilometers further east:

1) Japanese soldiers who had come were relatively healthy, and they had rested at this village for a few days before heading off on the eastern mountain road toward Chiang Mai. . . .

6) Near the end of the war, on average once a week, a group of soldiers would pass by on its way to Chiang Mai.55

SOURCE 3. The Etou Foundation (慧燈財団), in an early comment, reported:

In the final stages of the war in 1945, the Japanese military withdrew from Burma and returned through this area. When many died of malaria and related illnesses, their comrades buried them in the abandoned well at the San Khayom temple.56

This statement, however, appears to have been in error. As noted above, the sisters remember things differently: Soldiers who died around Ban Kat were originally buried on the grounds of Wat Maan, with remains disinterred years later when portions of remains were sought for returning to Japan, in accordance with Japanese custom.57 Only then were the rest of the remains put down the well. And, as has been noted, prior to the war,58 the well had been used for disposal of local bodies.

More recently, and unfortunately perpetuating that error, this author commented on the above:

A possible reason for this action was NOT to contaminate the well or the water table; rather it appears it might have been a matter of public health in dealing quickly with hundreds of bodies in a tropical environment. Military personnel were exhausted, hospital staffs were desperately overworked, and equipment was not available to dig the mass graves required. The well was dry and had been long abandoned: it was a convenient pre-existing hole which allowed the expeditious disposition of a very large health hazard.The hole would not have been considered for such use if it had been a working well. Since there were perhaps thousands of Japanese military passing through the area, it would not have made any sense at all to contaminate any well.(“Review Note 2” (03 Nov 2008) in Hardcastle, David, “How Japan has not forgotten: 63 years after The War”, City Life Chiang Mai (Nov 2008). Note: on-line archives are no longer available (comment: 21 May 2022).)

Curiously, there does not appear to be any Thai research published about this location.

Nov 1977: Partially supported by a Japanese Government financial grant, Japanese war veterans came to Ban Kat asking where the Japanese army had stayed and where the dead had been buried. They were directed to Wat Maan. Neither Wat San Khayom nor its well are mentioned in the final report of that effort.59

Jan – Mar 1978: The results of on-site research by the veterans were followed up by younger Japanese who retrieved what remains could be found, which eventually numbered 63.60

Portions of remains recovered were cremated with proper Buddhist ceremony and the ashes returned to Japan:61 the rest of the remains were relocated from the Wat Maan burial ground to the well at Wat San Khayom.

1989: Shirabe Kanga was one of several Buddhist monks who had gone to Cambodia to help refugees. On the way back, they met relatives of Japanese war dead from Saga Prefecture (located on the northwest coast of Kyushu, Japan’s southernmost main island), and went with them to Chiang Mai. In Chiang Mai at Wat Muen San, they met an old Thai monk who urged them to recover the remains of IJA troops

The new Witayacom High School serving Ban Kat was commissioned.62 During construction, the well was rediscovered along with its bones which had come from both local mayhem as well as the subsequent relocation of IJA remains.

1990: Shirabe Kanga, motivated by the Thai monk’s urging, began the search for IJA remains.63

1992: Per an Etou Foundation information leaflet about the memorial (as translated):

. . . a team from Japan started searching in this general area for the remains of Japanese soldiers from World War II. As a result, the remains were discovered at Wat San Khayom’s abandoned well, in addition to other areas. The well was located on the grounds of the current Ban Kat Witayacom High School.64

1993: The Japanese found the location of the well attractive: it was remote from the development in Bat Kat in an appropriately quiet, peaceful area. An Etou Foundation English-language information leaflet about the memorial notes:

. . . the executive director of Etou Foundation, Shirabe Kanga, a Japanese monk, along with the Japanese Consul General in Chiang Mai at that time, visited the high school, seeking permission to erect a stone monument to the soldiers lost in the Thai-Burma Campaign [over the well].

Seri Swanapet, the school principal (1990-1997), and responsible for the water well, gave permission for the foundation to occupy the site because of the presence of the remains of Japanese soldiers.65

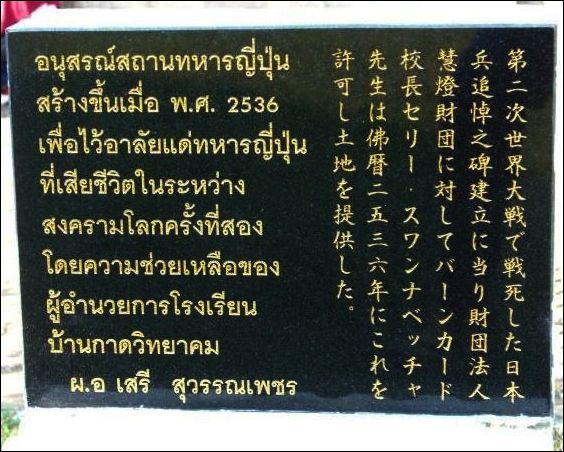

A bilingual Japanese-Thai sign at the entry point to the memorial area66

translates as:

In 1993, the principal of Ban Kat High School offered a plot of land to the Etou Foundation to build a monument to Japanese military personnel who died in World War II.67

1995: Etou Foundation was formally established by Shirabe Kanga to facilitate the collection of remains and the building of a memorial. An educational assistance / scholarship program was begun in the Ban Kat schools.68

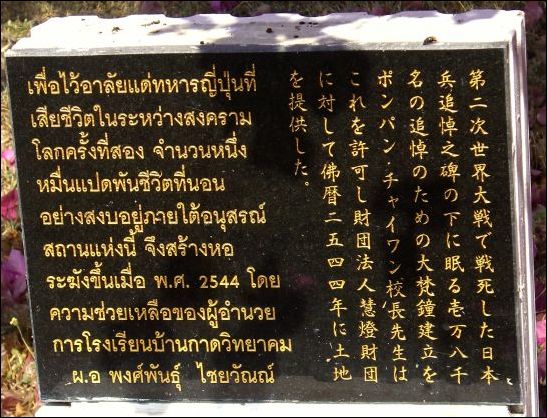

2001: A pedestal on the left side of the bell tower written in both Japanese and Thai69

translates as:

In 2001, the principal of Ban Kat High School gave permission to the Etou Foundation for construction of a bell tower in memory of Japanese military personnel who died in World War II.70

Etou Foundation website information about the memorial tells in translation that the bell and tower were constructed in 2002.

The 2011 ceremony was covered in detail in the Japanese language webpage, Etou Foundation News,71

However, there have been no entries since Feb 2012.

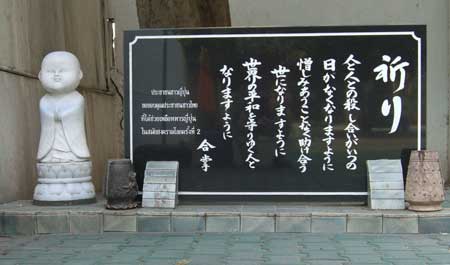

Date: Ongoing: Organized by the Etou Foundation, Remembrance Day Services are held annually at the memorial:72

Next: A tour of the Ban Kat Memorial Site

| First published on Internet | ||

| Converted to WordPress by Ally Taylor | ||

| Updated, author errors & typos corrected, and content expanded | ||

- or Taungoo[↩]

- บ้านกาด, ie, Ban Kat, is the Royal Thai Survey Department (RTSD) place name. It is also rendered in English as Ban Kad, Ban Gat[↩]

- Map is composite from แผนที่ทางหลวงประเทศไทย Scale 1:1,500,000 (กรุงเทพมหานคร:กรมทางหลวง, 2009) [Road Map of Thailand, Scale 1:1,500,000 (Bangkok: Department of Public Highways, 2009)], pp 2, 4, (hereafter Road Map) with annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher. Since accurate maps of the era are not consistently available, routes used by IJA forces are here assumed to have approximated currently existing roads. For reference purposes, the route is here described using modern highway designations where applicable. [my ref: 02320 00\Revised Ctrl rte map\Ban Kat alt locatn map.jpg][↩]

- There may have been some sort of rudimentary clinic at Ban Na Chon, but it is not well documented[↩]

- These distances were measured from Hon Khoai Island (Google Maps link) off the Vietnam Peninsula and heading either directly to Bangkok (Google Maps link), or Chumphon (Google Maps link) respectively. At the latter, cargo was transferred to rail cars for transport across the isthmus by the Kra Railway to Khao Fa Chi (Google Maps link), then reloaded on small cargo vessels for a coast-hugging trip to various Burmese ports as far as north as Rangoon. Distances are by Google Earth Ruler[↩]

- Sources: routing in most cases assumes that current roads approximate those used during WW2. Distances:

● Chiang Mai, Thailand to Kemapyu [now Khe Hpyu], Burma: rome2rio.com and Google Maps (depending on how closely the route chosen might resemble that in 1944)

●Kemapyu-Toungoo: The Motor Roads of Burma (Rangoon, The Burmah Oil Co, 1948). This last was required because neither rome2rio.com nor Google Maps recognize the old private road direct between Toungoo and Mawchi.

●Khun Yuam to Border Pt: no coverage — estimated using double the air distance (12 km) required 97 km of road improvement from Mae Taeng to Pai and 283 km of construction from Pai to the border west of Khun Yuam(Source of original map: Senshi Sosho vol 15 p141; annotation by author using Microsoft Publisher (my ref: \02300 Route CHOICES\02301 Summary maps\1943 route choices-colored\_MASTER Route choice map.pub\Sheet 2; (2nd choice) bPROJECT\_CNX Post articles\01-03 composite\02 PAI BRIDGE PART 2\Color maps\1943 choice of rtes to Burma-c.jpg) [↩]

- 戦史叢書 Vol 15:インパール作戦―ビルマの防衛 (東京: 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室 (編集), 1968年)[Senshi Sosho, vol 15: Imphal Maneuvers, Burma Defense (Tokyo: Defence Agency, National Defense College Military History Room, 1968)] (hereinafter “SS15“), p 140).[↩]

- Google Maps, annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher (my ref: \02300 Route choice\02300 Route CHOICES\02301 Summary maps\1943 route choices-colored\CNX-Toungoo.jpg (2nd choice: 02360 Khun Yuam\Map\Khun Yuam Hubbb.jpg) [↩]

- 戦史叢書 (東京: 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室 (編集), 1968年) インパール作戦―ビルマの防衛 (1968年) 防衛庁防衛研修所戦史室 (編集) [SENSHI SOSHO Vol 15: Imphal maneuvers – Burmese defense (1968) Defense Agency National Defense College military history room (compilation)], p 182; annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher (My ref: \02340 00 Maps\KOHIMA DOWN\Koh-Tgoo composite.jpg (\03302 015 Senshi Sosho vol 15 (Imphal op)\SS15 maps\ss15 p182.jpg) [↩]

- Google Map, annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher; my ref: \02300 Route choice\02300 Route CHOICES\02301 Summary maps\1943 route choices-colored\CNX-Toungoo.pub\sheet 8[↩]

- The Motor Roads of Burma, Fourth Edition (Rangoon: The Burmah Oil Co, 1948) [↩]

- A Bailey bridge would have to be a post-war detail since the first such bridge had been installed in Europe only after the Japanese had occupied Burma[↩]

- My ref: \02340 Burma connections\02340 B005 000 Toungoo – Kemapyu\Mawchi Mine.txt[↩]

- My ref: \02340 Burma connections\02340 B005 000 Toungoo – Kemapyu\Traveling Toungoo-Mawchi ~late 1940s.pdf[↩]

- Air Objective Folders by Target Area, Burma: South Area; Item Date: 1942-12-15; http://www.fold3.com/image/#26154893; my ref: \02300 Route choice\02340 Burma connections\02340 B005 000 Toungoo- Kemapyu\Mawchi Fold3\Mawchi.pub/pt Sht 1[↩]

- Part of Berndtson map “Thailand North” annotated by author using Microsoft Publisher; my ref: \02300 Route choice\02320 Central Route\02320 00 Maps\CNX markup map GEN1 CENTRAL RTES.pub\Sheet 4[↩]

- The 160 km is derived from the map in SOURCE 2 below.[↩]

- N18°36.530 E98°48.770[↩]

- “Details about the Monument Dedicated to Those Left Behind in the Thai-Burma Theatre”, Etou Foundation handout (undated, translated from Japanese).[↩]

- ibid[↩]

- Interview with Komloo and Yai Yin, lifelong residents of Ban Kat: with Kamloo on 29 Sep 2008 and with the two on 04 Oct 2009. Wiyada ‘Noi’ Kantarod was translator for both interviews. See below.[↩]

- In Thailand, Konishi Makoto (小西 誠) was a Japanese language teacher at the Ban Kat school. In that position, he had become well acquainted with the history that Ban Kat shared with Japan during and then after WWII. While maintaining his connections with the school, he had taken on responsibilities as manager of the Japanese War Memorial there. Since then, Konishi Makoto resigned his teaching position, trained a replacement for his manager function, and resigned that function as well, to further his education in Japan. He had been ‘discovered’ by Junko Kobata (コバタ ジュンコ), my first Japanese language tutor, who took an active interest in researching the history of the IJA in northern Thailand for this project. Author photo: CIMG3668a.jpg, 12 Sep 2008[↩]

- Family name missing.[↩]

- See map at top of page[↩]

- Ban Kat Soi 4/6 in Tambon Mae Wang (บัานกาด ซอย 4/6 เทศบาลตำบลแม่วาง).[↩]

- N18°35.865 E98°49.195[↩][↩]

- Author photo: CIMG5018a.jpg, 04 Oct 2009.[↩]

- The London Gazette makes no mention of the appointment of a British consul at Ban Kat; but does record the appointment of Hugh Randolph Bird as Consul for the Changvads, to reside in Chiang Mai:

(London Gazette,(external link) issue 34494, p 1840, 18 Mar 1938).[↩]

(London Gazette,(external link) issue 34494, p 1840, 18 Mar 1938).[↩] - N18°35.855 E98°49.235[↩]

- Some rice had been donated by sympathetic Thais. Some had been received as essentially wage for having helped Thais, typically farmers. Some had been harvested by the soldiers themselves as they traveled[↩]

- SS15, p 140[↩]

- 戦没者遺骨収集の記録 ピルマ・インド・タイ [Journal on Collection of Japanese War Dead: Burma, India, Thailand (Tokyo: All Burma Comrades Organization, 1980)], hereinafter “Journal“, p 450. Actual route is not clear; a Google Earth plot along current roads reads 115 km.[↩]

- Interview with Kamroo, 23 Oct 2008[↩]

- 井上 朝義 (えのうえもとよし),彷徨ビルマ戦線(山口県防府市: 大村印刷株式会社,昭和63) [Inoue, Motoyoshi, Wandering on the Burma Front (Hofu: Omura, 1988), p 169[↩]

- ชมธวัช, เชิดชาย, บ้อมูลเส้นทาง เดินทัพทหารญี่ปุ่นในอำเภอบุนยวม สงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา (สงครามโลกครั้งที2) จดทำโดย พันตำรวจโท [Chomthawat, Cherdchai, Information about Japanese Soldiers Traveling through Amphur Khun Yuam in World War II (self-published, undated)]. Information reported by Interviewee Nos. 2 and 6 (unpaginated).[↩]

- Mosaic of PointAsia views of Ban Kat area, accessed 05 Sep 2008. Annotations by author. Google Earth coverage was substantially inferior in resolution in 2009; in Mar 2012, resolution was satisfactory, but its imagery suffered from a peculiar color washout, so PointAsia view has been retained. The map has not been updated: no relevant features have changed since 2008. My ref: \02300 Route choice\02320 Central Route\02320 1013 008 Ban Kat\Maps\Ban Kat macro-aa.pub\Sheet 2, as Ban Kat macro-aaa-red.jpg[↩]

- N18°43.87 E98°28.60[↩]

- N18°35.875 E98°49.075[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3657a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3658a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Wat Maan ruin 1.jpg (13:29 11 Jun 2022) emailed by cnxpeter 16:52 17 Jun 2022[↩]

- Wat Maan ruin 4.jpg (13:31 11 Jun 2022) emailed by cnxpeter 16:57 17 Jun 2022[↩]

- gate on road at N18°36.55 E98°48.74[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3644a.jpg, 12 Sep 2008[↩]

- N18°35.71 E98°49.26[↩]

- N18°35.68 E98°49.17[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3654a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Author photo: CIMG3646a.jpg, 09 Sep 2008[↩]

- Journal, p 453 with annotations by author[↩]

- the name, Muan To, was also applied to Mae Hong Son town from 1917 to 1938[↩]

- N18°36.664 E98°50.862[↩]

- Journal[↩]

- Journal, p 450, annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher in conjunction with translators; My ref: \02300 Route choice\02320 Central Route\02320 00 Maps\IJA Routes, Ctrs\Central Rte.pub\Sheet 2, from 03300 JRNL COLLECTG IJA DEAD\Maps annotated\450 map anno.jpg[↩]

- Journal, p 422[↩]

- Journal, p 452[↩]

- Handout brochure for memorial service at Ban Kat, unpublished (Chiang Mai, Etou Foundation, Aug 2008); translation by author.[↩]

- “the cultural importance to every Japanese of returning some portion of a dead comrade’s body to his homeland”, as recorded by Max Hastings in Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 (New York: Knopf, 2008), p 78, hereinafter “Retribution”[↩]

- see above, section titled 1913-1941[↩]

- Journal, pp 419-470.[↩]

- Journal, p 470[↩]

- Journal, p 460 ff[↩]

- ข้อมูลทั่วไป (general information on website, www.bankad.ac.th, now a dead link). Per Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1), by 04 Jul 2012, this school info website had been expanded and historical info was available at History (link now dead). The commissioning date appears to have been 1987 (BE 2530).[↩]

- Per clarification in Konishi email of 18 Apr 2012 (Rev 1).[↩]

- “Details about the Monument Dedicated to Those Left Behind in the Thai-Burma Theatre”: from English language Etou Foundation handout for memorial ceremony on 24 Jul 2008.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- Author photo: cimg2236.jpg, 07 Jan 2008[↩]

- See section titled ‘2001 (BE 2544)’ below and footnote[↩]

- From “Etou Foundation Chronological History” in Japanese language at http://ww7.tiki.ne.p-~intuji-ensen.htm, accessed 16 Jul 2010; now unavailable (21 May 2022).[↩]

- Author photo: cimg2252.jpg, 07 Jan 2008[↩]

- Consistent with the Etou website’s History of the Memorial in Japanese (link no longer active).[↩]

- Etou Foundation News (external link) [↩]

- Tigerpix-uap-133.jpg, 24 Jul 2008. Courtesy of ‘Gus’ Gutteridge, Thaigerpics[↩]