1944

03 Jan 1944: CBI – THEATER OF OPERATIONS – CHINA (14AF): [From] China, 28 B-24s attacked the railroad yards at Lampang.1

This was the second major attack on the Lampang rail yards in four days.

This flight was escorted by two USAAF 449th Fighter Squadron P-38 Lightnings. Four Thai fighters sent up did not engage.2

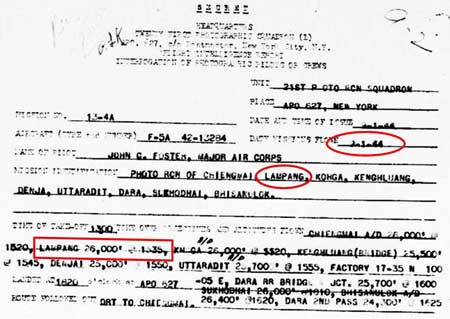

09 Jan 1944: In the first record currently available of an Allied surveillance aircraft overflight of Lampang, a USAAF P-38 (F-5A) outfitted with aerial photo equipment recorded the area from 26,000 feet (8000 m) at 1535 hrs:3

The flight path, as determined by the target locations, followed the railroad — aside from Ko Kha, a satellite airstrip about 13 km southwest of the Lampang airport. No aerial photography related to this particular report has been found as of 30 September 2013.

Allied intel’s Airfield Report for January 1944 included only this information about Lampang — an airfield miniature summary:4

But note that “Shelters” had increased from 37 reported in November 1943 to 49 here in January 1944. The increase was in keeping with this observation noted in the January 1944 Airfield Report of general improvements:5

As with previous corrections noted, it is unfortunately unclear which previous report this was intended to corrected.

24 January 1944: Aerial reconnaissance observed no aircraft on this date, per a note in a consolidated report in Dec 1943.

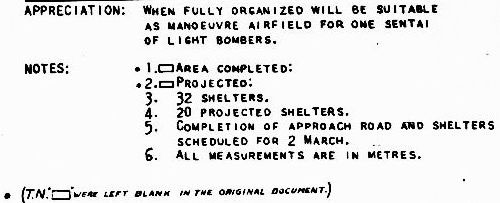

01 Feb 1944: This sketch of Lampang Airfield has been reoriented so that north is top-of-page (the north arrow on the sketch is in error) to ease comparison amongst all maps.6 Annotations merely clarify hard-to-read text in the sketch. Applicable notes from the bottom of the original sketch follow;7 coding in the map sketch is incomplete as stated on the last line.

Comments:

One sentai of light bombers: “up to 30 aircraft”.8

Note 5, “Completion of approach road and shelters scheduled for 2 March” strongly implies that there was an intelligence source on the ground.

Conversely, note that the sketch here does not conform well with that of the miniature above, nor the aerial photos dated 22 October 1943 and 15 November 1943. The sketch’s crudity, and its lack of similarity to aerial photos and other sketches, suggests again that the information for it was not provided by an on-the-ground source.

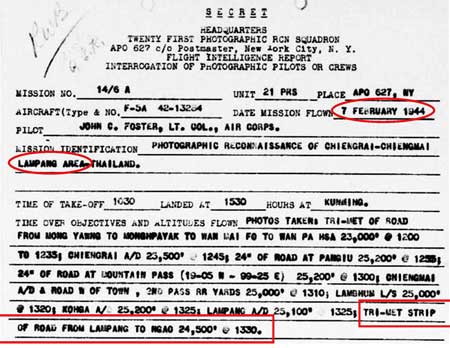

07 Feb 1944: Aerial photos were taken at Lampang plus about 85 km along the roadway north9 to Ngao10 (Google Maps link): this road eventually reaches the border crossing into Burma at Mae Sai / Tachileik (in all, about 290 km distant from Lampang):11

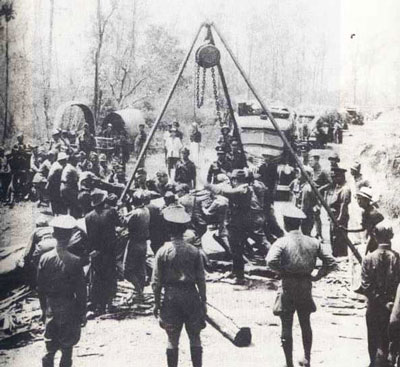

Sighting activity on the ground similar to this from the air may have initiated the order for surveillance of the road north from Lampang:12

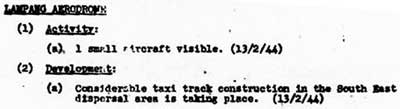

The Allied intel monthly report on enemy airstrips noted that, though only one “small” aircraft was recorded as observed, construction work continued:13

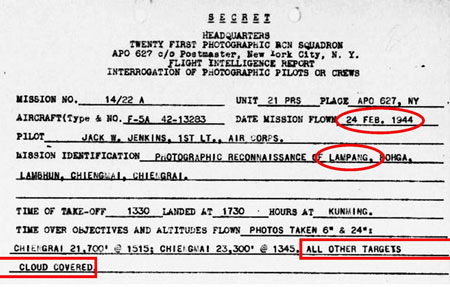

24 Feb 1944: Lampang was cloud-covered this day for aerial photo purposes:14

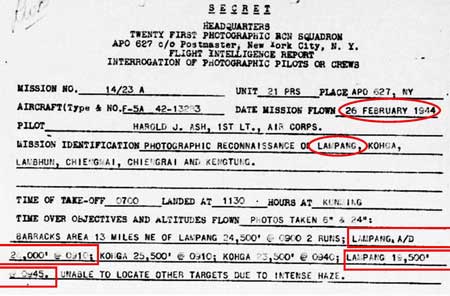

26 Feb 1944: Aerial photos were taken of Lampang A/D (airdrome) and Lampang (presumably the city):15

06 March 1944: 900 km northwest of Lampang, IJA Operation U Go (offsite link), the attempted invasion of India, began with an attack at Imphal.

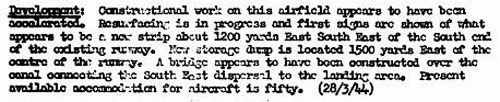

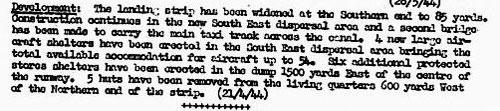

28 March 1944: Construction activity at Lampang appeared to have been quite intense when this observation was made. Most important potentially was the appearance of a separate airstrip newly under construction 1,200 yards (1,100 m) to the ESE of the south end of the existing runway; however, this was never mentioned again and might have been referring to one leg of an extensive taxiway / “taxi track” system to the east of the north-south runway:16

No orientation was given for that “new strip”: if it were a new strip and not a taxiway, it might have been intended as a parallel runway, the philosophy of which was described by Allied intel for a later satellite air facility, Hang Chat, in a September 1944 entry.

Note that resurfacing was clarified in the following month’s report with the runway surface defined as rolled earth; probably “resurfacing” for the dirt runway consisted of “smoothing”; ie, low spots and rutting were filled in, fill edges were feathered out, and the whole of the runway was then rolled. It is curious that such work was performed just prior to the onset of the rainy season; normally such remedial work was conducted after the ravages of a rainy season. This therefore might have been done in anticipation of providing support for the IJA’s imminent attempt to invade India.

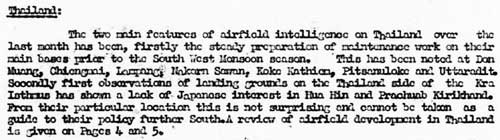

April 1944: The Airfield Report for this month included some substantial analyses. Regarding Lampang were “Comments on Current Development”, which offered some perspective on local conditions in Thailand:17

TRANSCRIPT (of relevant portion):

The . . . main [feature] of aircraft intelligence on Thailand over the last month has been . . . the steady preparation of maintenance work on their main bases prior to the southwest monsoon season. This has been noted at:

Don Muang18 (Google Maps link)

Chiang Mai19 (Google Maps link)

Lampang20

Nakhon Sawan 21 (Google Maps link)

Khok Kathiam22 (Google Maps link)

Phitsanulok23(Google Maps link)

Uttaradit 24 (Google Maps link). . . .

From this, it would appear that Allied intelligence was attributing maintenance work on airfields solely to anticipated weather (Note that Takhli Airfield25 (Google Maps link) was not included: construction was not completed until 06 September and then it was turned over to the IJAAF).

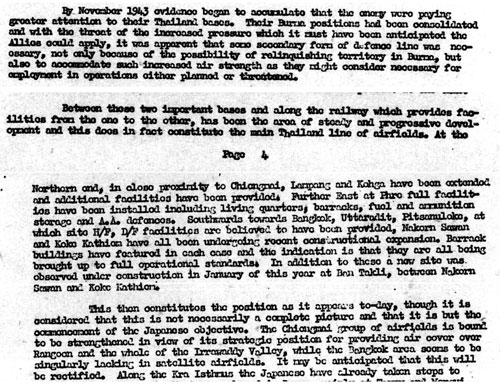

However, that view was modified on the next page of the report in an analysis titled “Review of Airfield Development in Thailand”:26

TRANSCRIPT of relevant parts, (emphasis mine):

By November 1943 evidence began to accumulate that the enemy were paying greater attention to their Thailand bases. Their Burma positions had been consolidated and with the threat of the increased pressure which it must have been anticipated the Allies could apply, it was apparent that some secondary form of defence line was necessary, not only because of the possibility of relinquishing territory in Burma, but also to accommodate such increased air strength as they might consider necessary for employment in operations either planned or threatened. . . .

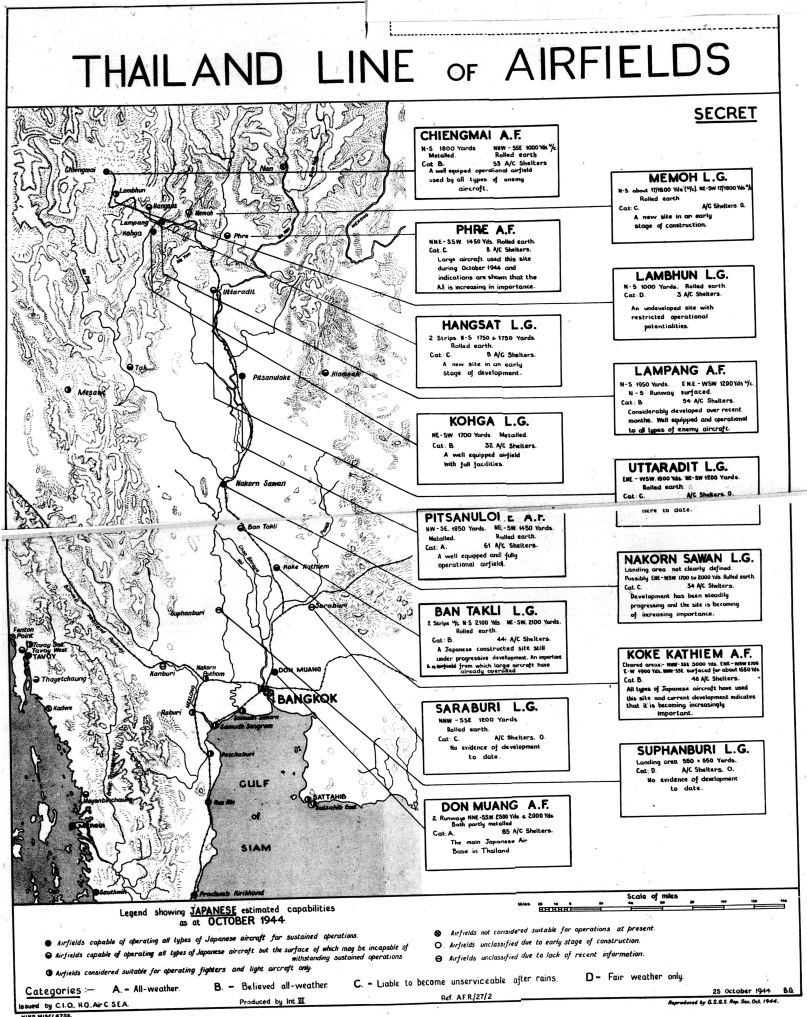

. . . Between these two important bases [of Chiang Mai and Bangkok] and along the railway which provides facilities from the one to the other, has been the area of steady and progressive development and this does in fact constitute the main Thailand line of airfields. At the northern end, in close proximity to Chiang Mai, Lampang and Ko Kha [runways] have been extended and additional facilities have been provided. . . .

This then constitutes the position as it appears today, though it is considered that this is not necessarily a complete picture and that it is but the commencement of the Japanese objective. The Chiang Mai group of airfields is bound to be strengthened in view of its strategic position for providing air cover over Rangoon and the whole of the Irrawaddy Valley . . . .

Note that this review was prepared before the IJA’s offensive effort to invade India. At the mentioned date, November 1943, the IJA had just designated Lampang as a transfer point for troops and supplies moving towards the invasion point in Burma — north by rail from Bangkok to Lampang; thereafter by foot or vehicle on the road north through the Thai-Burma border towns, Mae Sai and Tachileik; on to Kengtung and Mandalay in Burma; and finally northwest to assembly points for the IJA invasion of India.

While evaluating Thai airfield improvements as possibly to “accommodate . . . increased air strength”, Allied intelligence, in noting the many aircraft at Bangkok at this time, seemed to fail to consider the consistent lack of aircraft reported on airfields in the northwest of Thailand: for example, despite 32 aircraft shelters at Ko Kha, no aircraft were ever sighted there. Having 50 shelters, Lampang was never recorded with many aircraft sighted, save for 15 November 1943 (and this dearth continued with the next report, of 21 April 1944, though this would apparently have been a testimony to the success of the RTAF, and possibly the IJAAF, in hiding aircraft since RTAF Squadrons 11, 12, 16, and 62 plus possible IJAAF units were located there). The point here is that Allied intel did not seem aware of an absolute decrease in number of IJAAF aircraft because of an inability of Japanese factories to produce sufficient aircraft to replace those lost in battle.

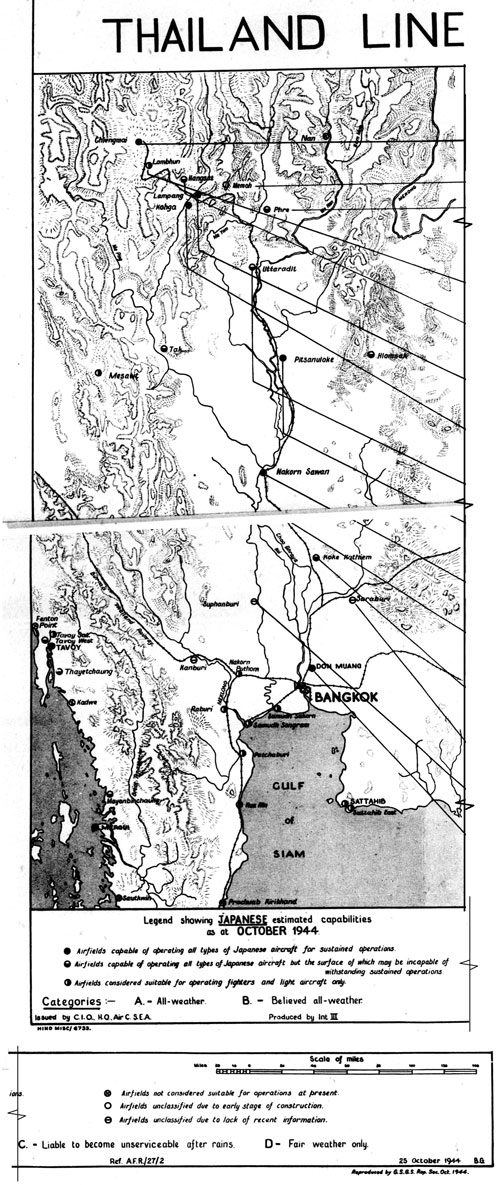

An important concept was first presented in the transcript above: the main Thailand line of airfields. The phrase would be graphically presented in October 1944’s Airfield Report.

21 April 1944: Surveillance was becoming more consistent and never found more than “two or three aircraft” at Lampang:27

Numerous improvements were being implemented at the airfield; four more aircraft shelters had been added to bring the total to 54:28

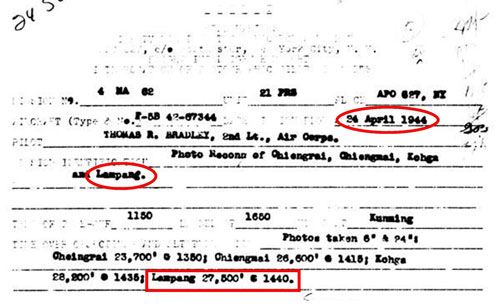

24 Apr 1944: Lampang was “covered” by aerial photography:29

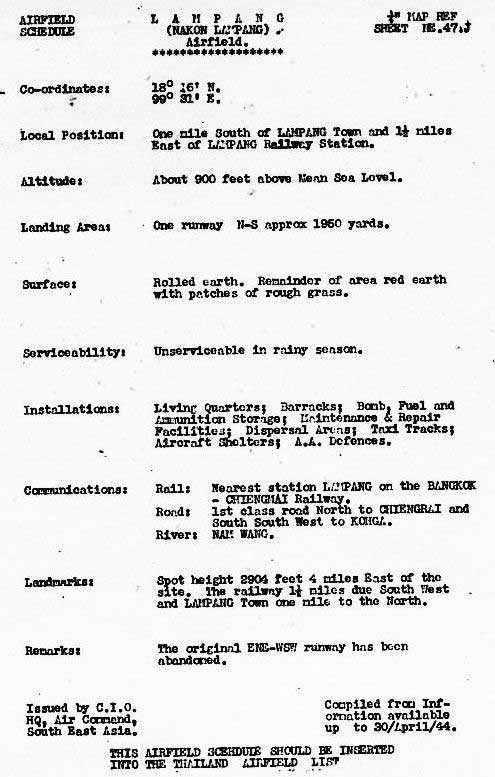

30 April 1944: In the April Airfield Report was a more formal and detailed presentation about the facility, evidencing a growing sophistication in Allied intelligence gathering and reporting:30

A key detail to note: the 28 March 1944 report described “resurfacing” in progress, which this report a month later clarified: the surface was rolled earth and “unserviceable in rainy season”. Curiously, the Ko Kha airstrip, assumed by Allied intel to be a satellite of Lampang, was “metaled”; ie, surfaced with crushed stone, and truly all-weather.31

The Remarks conclude the original ENE-WSW runway had been “abandoned”: there is no specific information currently available about the original runway and its alignment in the March 1940 entry, though that information’s general nature suggests that the airfield probably conformed to an earlier standard of being circular, per Wikipedia Aerodrome (offsite link). A November 1943 remark had mentioned that a ENE-WSW runway had been “probably abandoned” and attributed the runway to a Japanese effort, not Thai (ironically the ENE-WSW runway next appears in January 1945 with Note that the runway had been “revived and extended” with a length of 1400 yards under construction).

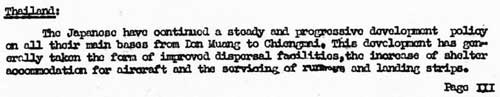

May 1944: Detailing of airfield improvements continued in Allied reporting:32

Transcript:

The Japanese have continued a steady and progressive development policy on all their main bases from Don Muang to Chiang Mai. This development has generally taken the form of improved dispersal facilities, the increase of shelter accommodation for aircraft and the servicing of runways and landing strips.

And was supplemented by this additional report:33

TRANSCRIPT of second report above reads in part:

Red earth, with patches of rough grass; f/w [fair weather].

Runway being hard-surfaced; believed a/w [all weather].

Rolled earth strip u/c [under construction] 3600′ ESE of S end of runway.

([Date of observations] May 44).

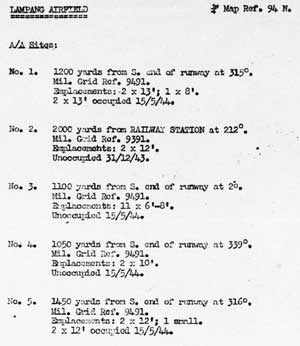

15 May 1944: Five anti-aircraft emplacements were noted around the airfield, only two of which were evaluated as armed:34

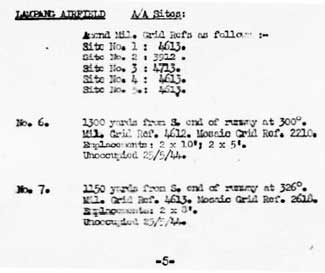

25 May 1944: Construction of an additional two new anti-aircraft gun emplacements (numbers 6 and 7) was recorded, neither one armed.35

While the locations may appear well defined, they suffer from three major sources of error:

One, the south end of the runway is used as a reference point in locating six of the seven emplacements. The south end is itself not clearly defined.

Two, distances appear to be stated to the nearest 50 yard increment, that is, ±25 yards. To give that some perspective, the width between painted margins on the current runway at Lampang measures 13 yards; so, accuracy is plus or minus two runway widths.

Three, the bearings are measured from true north; however, with the bearing of the runway assumed constant and with a current true bearing of 355°, per Google Earth, a comparison of north arrows among different views of the airfield finds significant differences between what is used as “true” north.36

28 May 1944: It is not clear whether two aircraft were observed, one on 25 April and the other on 15 May; or whether both aircraft were seen on those two dates:16

Transcript:

Activity: Steady reconnaissance has indicated very little activity at this airfield. 2 small aircraft however, were observed on 25th April and 15th May. (28/5/44)

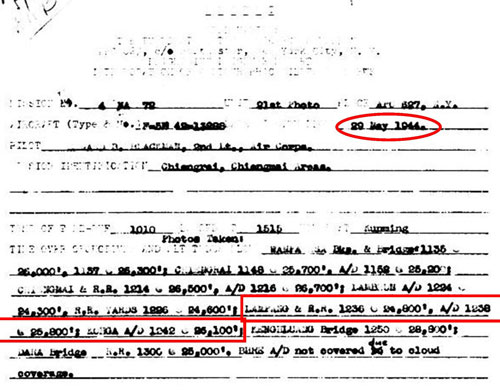

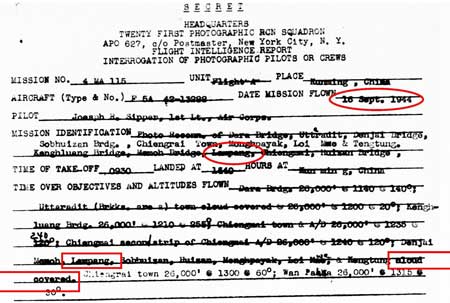

29 May 1944: Report of an aerial photo operation which overflew Lampang, among other locations:37

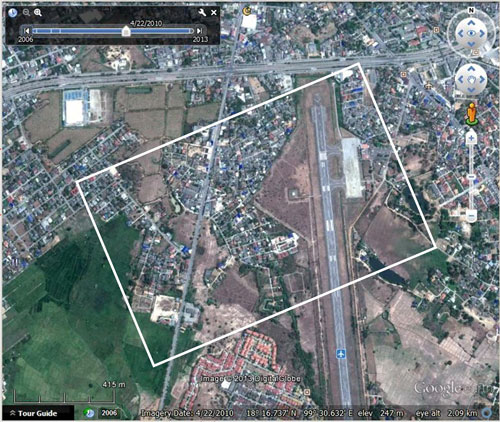

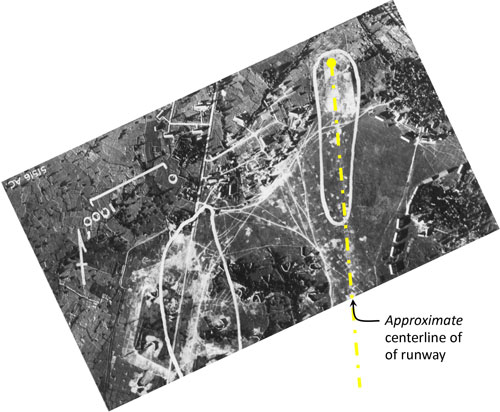

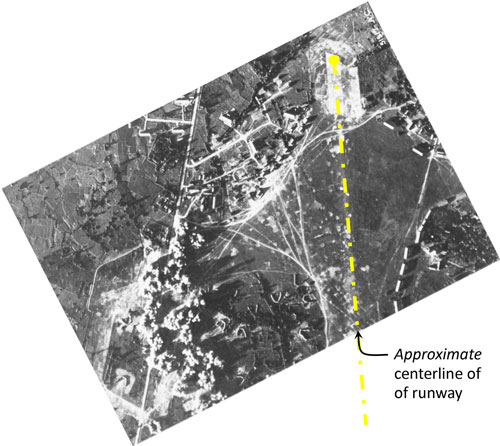

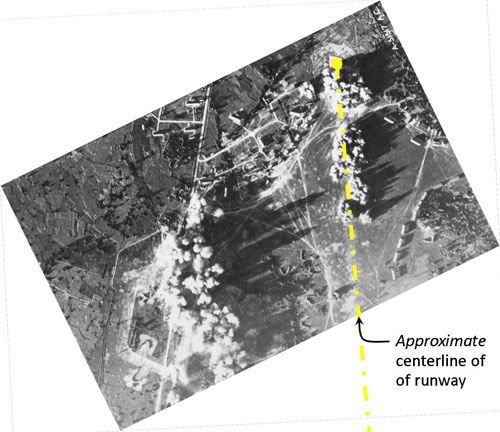

June 1944: Attack on Lampang: With date unspecified, the following series of three photos titled “War Theatre #11 (Lampang A/F, Thailand) – BOMBING” was released for publication on 23 June 1944.38 Photos have been reoriented to north-top-of-page and scales standardized amongst the three.

Location of the three is in the area of the north end of the current N-S runway as outlined below in white, which seems to coincide with that of the WW2 runway:39

Photo 1 of 3: Original caption: Lampang Airfield, Thailand was target for one of the 7th Group’s most effective missions. Two squadrons were briefed to bomb parking area [at lower left], third, runways, and fourth, installations at end of runway [upper right].40

Photo 2 of 3: Original caption: Bombing of Lampang Airfield, Thailand.41

Photo 3 of 3: Original caption: Bombing of Lampang Airfield, Thailand after last two squadrons had attacked. Installation and runway had been neatly pinpointed.42

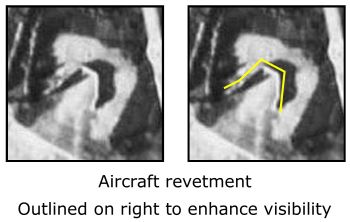

The various features in the three photos above, looking similar to “U” or “V” in different orientations, were aircraft shelters. For further analysis of the detail in the photos, see discussion under January 1945.

Here is a substantial enlargement from one of the aerial photos above of a typical aircraft shelter / revetment:43

Curiously, the USAAF Chronology for 1944 does not mention any activity near this time around Lampang.

July 1944: Per Japanese Monograph No 177, “Outline of Army Disposition in July 1944”:

161st Independent Infantry Battalion [was] stationed at Lampang in Northern Thailand and responsible for security in the area. . . .44

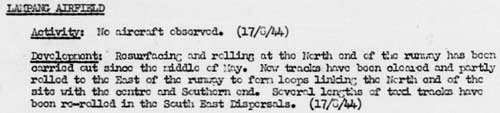

17 August 1944: Improvements continued at the Lampang airfield:45

TRANSCRIPT:

Lampang Airfield:

Activity: No aircraft observed. (17/8/44)

Development: Resurfacing and rolling at the north end of the runway have been carried out since the middle of May. New tracks have been cleared and partly rolled to the east of the runway to form loops linking the north end of the site with the centre and southern end. Several lengths of taxi tracks have been re-rolled in the southeast dispersals. (17/8/44)

16 September 1944: an aerial photo aircraft overflew Lampang, but “cloud cover” prevented photography:46

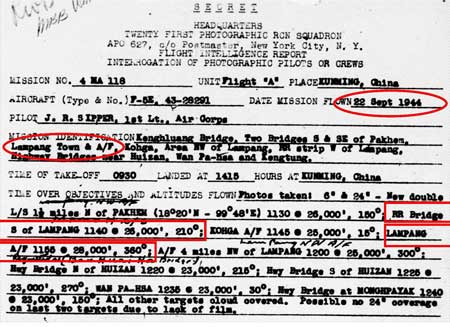

22 September 1944: While the aerial photo mission targeted Lampang town and airport, it reported photographing a railroad bridge south of the town (1140 hrs) plus the airfield (1155 hrs):47

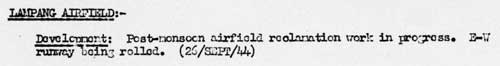

26 September 1944: The Allied Intel monthly report again recorded continuing routine maintenance:48

TRANSCRIPT:

Lampang Airfield

Development: Post-monsoon airfield reclamation work in progress. E-W runway being rolled. (26/SEPT/44)

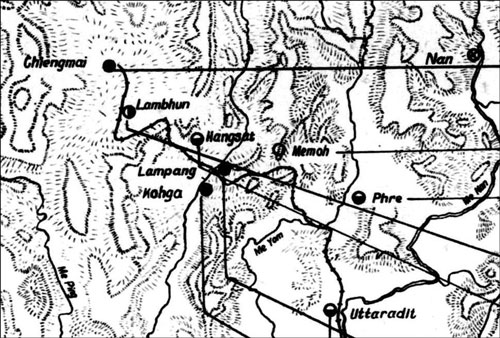

October 1944: Allied intelligence views of Japanese strategy had been presented in April 1944 and, though written before the IJA’s failed attack at Kohima and Imphal in India, it proved prescient in introducing the phrase, main Thailand line of airfields, to describe a potential IJA line of support for Burma and defense from Allied air attacks. Clarification in the form of a map entitled “Thailand Line of Airfields” only appeared six months later in the October Airfield Report:49

The map itself in more detail:50

And a yet closer view of northwest Thailand in that map:50

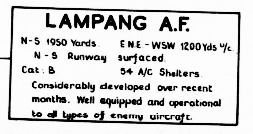

The information block for Lampang on the “Thailand Line” map reads:50

Transcript:

LAMPANG AF

N-S 1950 yards

ENE-WSW 1200 yards u/c [under construction]

N-S Runway surfaced [with what is not clear]

Cat: B [Category B: believed all weather]

54 A/C [aircraft] shelters

Considerably developed over recent month. Well equipped and operational to all types of enemy aircraft

Note that “Shelters” had not increased from the 54 noted in 21 April 1944 above.

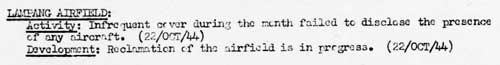

22 October 1944: The Allies’ monthly report on enemy air facilities implied that the lack of aircraft observed at Lampang was a function of “infrequent” coverage during the month. Work to repair rainy season damage was seen to continue:51

Transcript:

Lampang Airfield

Activity: Infrequent cover during the month failed to disclose the presence of any aircraft. (20/Oct/44)

Development: Reclamation of the airfield is in progress. (22/Oct/44)

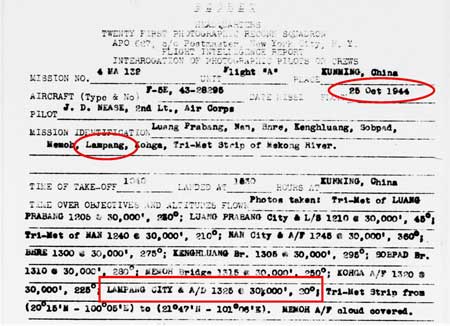

25 October 1944: a USAAF aerial photo outfitted P-38 (F-5E) photographed Lampang “city” (1325 hrs):52

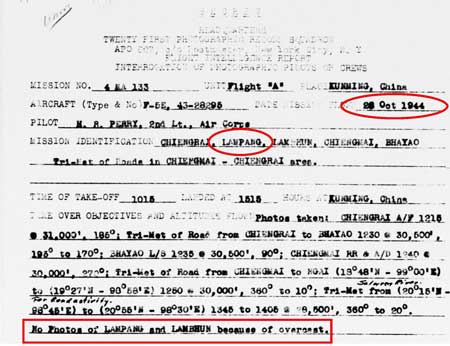

26 October 1944: a USAAF aerial photo outfitted P-38 (F-5E) assigned to photograph Lampang was prevented by “overcast”:53

05 November 1944: A USAAF reconnaissance aircraft fatally crashed in a thunderstorm south of Lampang with pilot, Franklin McKinney.

The USAAF Chronology showed no activity around Lampang on this date: chronologies typically did not cover intelligence gathering flights.

11 November 1944: From the USAAF Chronology:

CBI – THEATER OF OPERATIONS – CHINA (14AF):

. . . 70+ P-40s, P-51s and P-38s over S China and N Indochina on armed reconnaissance hit targets of opportunity at several locations, concentrating on Lampang, Thailand, and the Changsha, Lingling, and Hengyang, China areas.54

Jan Forsgren added:

. . . nine P-51 Mustangs from the 25th FS and eight P-38 Lightnings flew an offensive reconnaissance mission over northern Thailand. Their targets included the railway line between Chiang Mai and the Ban Dara bridge, as well as the airfields in the area. A locomotive was attacked, and damaged, and the American fighters also attacked Lampang airfield, destroying a single-engined aircraft on the runway.55

Five Ki-27bs from RTAF Squadron 16 at Lampang engaged them. In one dogfight, RTAF Pilot Officer Kamrop Bleangkam was credited with the shootdown of a P-51. All five Thai aircraft were shot down; four of the pilots were wounded, and one, CWO Nat Sunthorn, soon died of burns sustained after his Ki-27 was shot and caught fire.56

The USAAF fighter aircraft (the P-51 reported shot down above) was apparently downed by RTAF Pilot Officer Kamrop Bleangkam in a dogfight east of Lampang with pilot, Lt Henry Minco, killed in the crash.

More information about the encounter is available in the “Useful References” at the end of 11 Nov 1944: USAAF P-51 Crashed Near Lampang. Daniel Jackson’s Fallen Tigers offers a detailed reconstruction of the battle.

Young summarized:

The American fighters flew ten more missions over northern Thailand during the month [November 1944], and on five of these they strafed the airfields at Chiang Mai, Lampang, and Chiang Rai.57

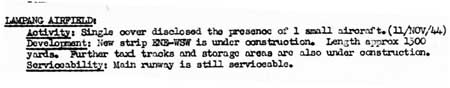

The Airfield Report for the month recorded through 11 November 1944:58

TRANSCRIPT:

LAMPANG AIRFIELD:

Activity: Single cover disclosed the presence of 1 small aircraft (11/NOV/44)

Development: New strip ENE-WSW is under construction. Length approx 1300 yards. Further taxi tracks and storage areas are also under construction.

Serviceability: Main runway is still serviceable.

Photographic Interpretation Review No. LB/4 revealed:59

Transcript:

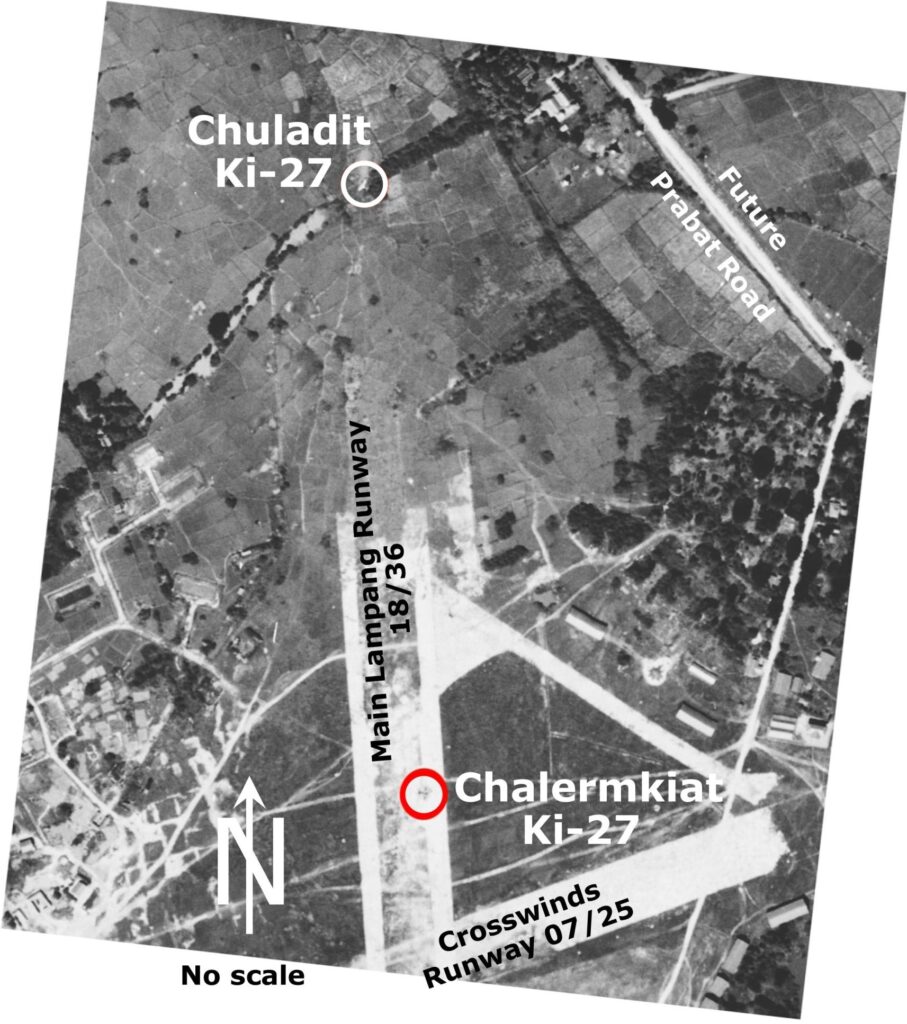

Lampang: A Nate is seen taxying on to the runway on cover of 11/Nov/44.

Intrigued by a coincidence of dates, 11 Nov 1944 being that of numerous dogfights around Lampang, Dan Jackson followed up on that report, got a copy of an aerial recon photo, and found a plane on the runway that would have been that of Flt Lt Chalermkiat Watanangura. His Ki-27 had been damaged in a dogfight forcing him to land. Moments after he landed and this photo was taken, Allied aircraft strafed the plane and it exploded (Chalermkiat was wounded, but survived). Also visible in the photo was the Ki-27 of Flt Sgt 3rd Class Chuladit Detkunchorn, north of the airfield, which had flipped over in a ditch after an emergency landing (Chuladit was injured, but survived).60

Aerial recon photo of Lampang airfield on 11 November 194461

Allied intelligence published a detailed map sketch of Lampang Airfield dated 11 Nov 1944 in the January 1945 issue of its Airfield Report which is discussed in detail in the January 1945 entry.62

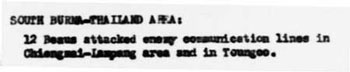

14 November 1944: Attack on Lampang:63

TRANSCRIPT:

12 Beau [Beaufighters] attacked enemy communication lines in Chiang Mai-Lampang area . . .

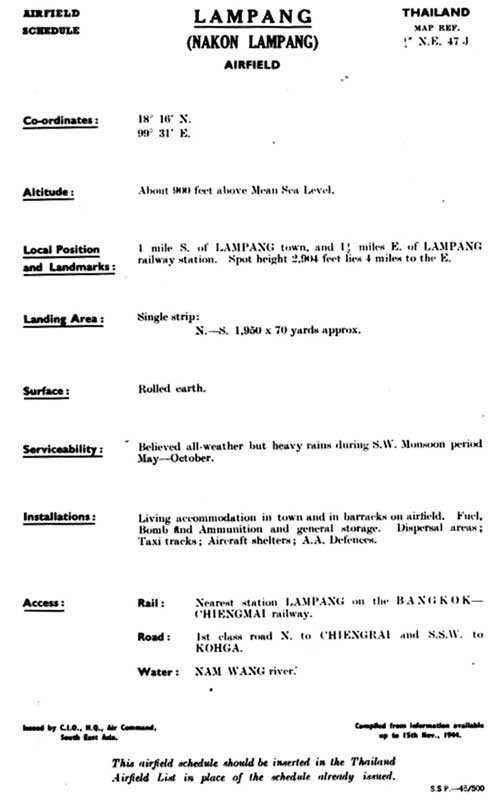

15 November 1944: Another detailed report on the airfield, with little new information, but with format further sophisticated: the report appears to have been printed, in contrast to the previous report (30 April 1944), which had been typed and probably mimeographed:64

There appears to be an inconsistency here: with a surface of “rolled earth”, the serviceability was nonetheless “believed all-weather”. Elsewhere “metalled” surfaces generally seemed to have been the only type rated “all-weather”.

23 November 1944:

Information about the photo reads in part:65

Salbani, Bengal, India. 1944-11-23. Informal group portrait of RAAF members of No. 355 (Liberator) Squadron RAF being briefed by Wing Commander (Wg Cdr) J. Martin DFC, RAF, for a mission against Lampang, railhead for the road running into the Shan States through Chiengmai in Thailand.

The above description of the mission is somewhat garbled: Lampang was the target. However, the railhead for the Thai Railway was at Chiang Mai, north of Lampang. Nonetheless, the main road connecting to the Shan States, ie, Kengtung, ran north from Lampang through Mai Sai, not Chiang Mai.

25 November 1944: CBI – THEATER OF OPERATIONS – CHINA (14AF):

. . . 75 P-40s, P-51s, and P-38s on armed reconnaissance attack river, road, and rail traffic, troops, buildings, and other targets of opportunity at several Thailand, Burma, S China, and N French Indochina locations, including areas around Bhre [Phrae] and Lampang, Thailand . . . .54

27 November 1944:

TRANSCRIPT, as relevant:66

THAILAND AREA:

15 Liberators dropped 39 tons bombs over loco [locomotive] sheds — Chiang Mai-Lampang area causing large fires. Meager and inaccurate light AA [anti-aircraft fire] encountered . . . .

From CBI – THEATER OF OPERATIONS – CHINA (14AF):

. . . 56 P-40s, P-51s, and P-38s on armed reconnaissance over E Burma, N French Indochina, and vast areas of S China attack town areas, railroad targets, bridges and other targets of opportunity around Lampang, Thailand . . . .54

30 November 1944: Five P-38s and four P-51s destroyed what was possibly a Squadron 62 Ki-21 heavy bomber while strafing the Lampang Airfield.67

December 1944: Young summarized:

. . . Allied air raids continued into December, with fighters and heavy bombers flying twelve missions, there were no further encounters with the Thai Air Force.68

03 December 1944:

The relevant text above reads:69

Rail targets at . . . the Chiengmai-Lampang rail sections were attacked by RAF Liberators. . . .

07 December 1944: Circumstantial evidence indicates that a USAAF P-51 crashed in the Lampang area with pilot, Thomas Ankrim, killed.

The USAAF chronology recorded no action over Thailand on 07 December 1944.54

08 December 1944: Japanese Monograph No 177 recalled:

. . . the [IJA] Southern Army received orders from Imperial General Headquarters to reorganize the [Siam] Garrison [Command] into the 39th Army. On the same day, the [Siam] Garrison [Command] was redesignated the 39th Army with no change in mission.70

26 December 1944: From USAAF Chronology:

26 December 1944: CBI – THEATER OF OPERATIONS – CHINA (14AF): . . . 46 P-51s, P-38s, and P-40s hit railroad targets, shipping, storage and other targets of opportunity at or near Kinkiang, Anking, and Ka-chun, China; Lampang, Thailand . . . .71

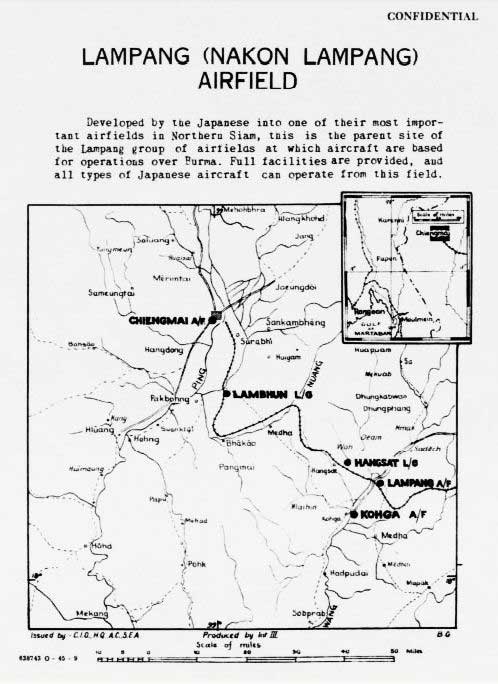

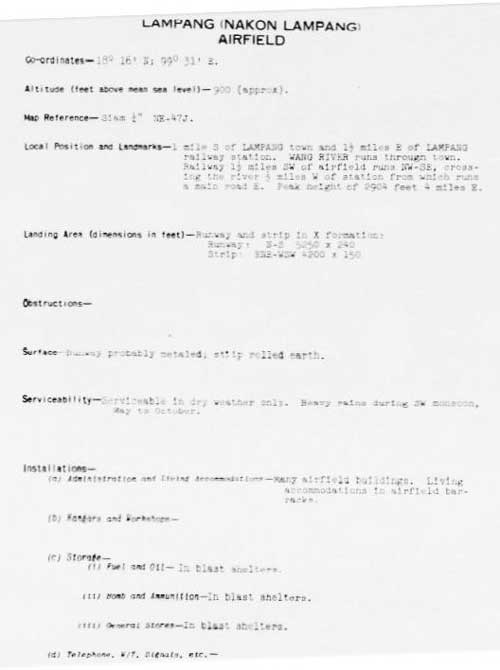

31 December 1944: An area map led the report on the airfield at the end of 1944:72

TRANSCRIPT:

Coordinates — 18°16N; 99°31E

Altitude (feet above mean sea level) — 900 (approximately)

Map Reference — Siam 1/4″ NE-47J

Local Position and Landmarks — 1 mile south of Lampang town and 1‑1/2 miles east of Lampang railway station. Wang River runs through town. Railway 1‑1/2 miles southwest of airfield runs NW-SE, crossing the river 1/2 mile west of station from which runs a main road east. Peak height of 2904 feet 4 miles east.

Landing Area (dimensions in feet) — Runway and strip in X formation:

Runway: N-S 5250 x 240 Strip ENE-WSW 4200 x 150

Obstructions —

Surface — Runway probably metaled, strip rolled earth.

Serviceability — Serviceable in dry weather only. Heavy rains during SW monsoon, May to October.

Installations —

(a) Administration and Living Accommodations — Many airfield

buildings. Living accommodations in airfield barracks.

(b) Hangars and Workshops —

(c) Storage —

(i) Fuel and Oil — In blast shelters.

(ii) Bomb and Ammunition — In blast shelters.

(iii) General Stores — In blast shelters.

(d) Telephone, W/T, Signals, etc —

(e) Night Landing —

(f) Water —

Aircraft Dispersal —

(a) Dispersal Areas —

Local: Meager.

Southeast: Moderate.

Southwest: Extensive.

(b) Aircraft Shelters: — See “Record of Major Development”

overleaf.

Defenses — See current report on “Japanese AA Defenses”

Access —

(a) Rail — Nearest railway station Lampang (1 1/2 miles west)

on main Bangkok-Chiang Mai railway.

(b) Road — First-class road NNE to Chiang Mai and SSW to [Ko Kha].

(c) Water — Wang River.

Next: Lampang Airport 1945

Last Updated on 13 December 2025

- The Official Chronology of the US Army Airforce in World War II, 1944 (unpaginated), hereafter USAAF Chrono 1944.[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 201.[↩]

- 21st Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron (hereafter 21PRS) Report Mission No. 13-4A, 09 Jan 1944 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A0878 p 0197). The aerial photo reconnaissance reports included here record coverage of Lampang by only the 21st Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron (21PRS) starting in January 1944. Other Allied units provided similar coverage, but I’ve not found their flight records (Nov 2012). Note that similar records/orders would have existed for previous aerial photos, eg, those on 22 Oct 1943, 15 Nov 1943, 25 Dec 1943, and for photos, not available, but used for intelligence development.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 18, Jan 1944, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 422).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 18, Jan 1944, p 36 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 475).[↩]

- Publication No. 3.II: Plans of Airfields in French Indo-China and Siam (?: Southeast Asia Translation and Interrogation Center 30 Nov 1944), unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8023 p 454). Annotations are by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- ibid, extract, rotated.[↩]

- Wikipedia, Imperial Japanese Army Air Service: Operational Organization (offsite link).[↩]

- Phahonyothin Road (future Thai Route 1[↩]

- N18°45.18 E99°58.70[↩]

- Distances per A2Z Atlas of Northern Thailand (Bangkok: PN Map Center, 2006), pp 2, 16. 21PRS Report Mission No. 14/6 A, 07 Feb 1944 (USAF archive microfilm reel A0878 p 0155).[↩]

- Photo from Axis History Forum (while that forum is still very active, the photo was unfortunately entrusted to Photobucket. Wisarut Bholsithi in that forum on 21 Jun 2004 suggested the probable locale for the photo: the main road between Lampang and Mae Sai on the border with Burma.

He also indicated that the work pictured would likely have occurred during 1942-1943 to facilitate RTA troop movement to the eastern part of Shan State in 1942 or IJA troop movement beginning in Nov 1943 towards western Burma in support of its attempted invasion of India in early 1944. The latter would apply here.

No aerial photo flight reports are currently available prior to Jan 1944; so this report was perhaps a continuation of an effort to monitor activity along the road. On the other hand, no mention of such activity is made in any Allied report (currently available) prior to this time.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 19, Feb 1944, p 24 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 524). The “small” aircraft periodically recorded might have been a mail plane that connected Lampang, RTA facilities in Burma, and Bangkok in the south via Phrae and Phitsanulok, described by Young, ibid, p 216.[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 14/22 A, 24 Feb 1944 (USAF archive microfilm reel A0878 p 0122).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 14/23 A, 26 Feb 1944 (USAF archive microfilm reel A0878 p 0118).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 22, May 1944, p 14 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 752).[↩][↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, p 3 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 679).[↩]

- N13°54.80 E100°36.34[↩]

- N18°46.32 E98°57.76[↩]

- N18°16.33 E99°30.24[↩]

- N15°40.35 E100°8.16[↩]

- N14°52.27 E100°39.45[↩]

- N16°46.41 E100°16.86[↩]

- N17°37.51 E100°05.51[↩]

- N15°16.60 E100°17.75[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, p 3 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 pp 0680-0688).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, p XVII (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 0713).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 22, May 1944, p 14 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 0752).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 62, 24 Apr 1944 (USAF archive microfilm reel A0878 p 0050).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 21, Apr 1944, unnumbered page (USAF archive microfilm reel A8055 p 0669).[↩]

- See discussion of term: metaled road.[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 22, May 1944, p III (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p 728).[↩]

- Provisional Airfield List: Southeast Asia, Enemy Airfield Information, Report No. 3 (Washington: Office of Assistant Chief of Air Staff, 2? Jul 1944) p 62 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A1284 p1412 (rpt start p1349).[↩]

- Record of Japanese Anti Aircraft Defenses, “Thailand: Alphabetical List of Main Target Areas” (?: CIO, HQ, AC, SEA, Jun 1944 ?), unnumbered page – USAF Archive microfilm reel A8063 p 399. Quality of accompanying aerial photo on p 400 too poor to reproduce.[↩]

- Record of Japanese Anti Aircraft Defenses, “Amendments to Target Areas” (?: CIO, HQ, AC, SEA, Jul 1944(?), p 5 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8063 p 168).[↩]

- In the late 1960s, I enjoyed hiking in the mountains overlooking Japan’s Inland Sea from Iwakuni to Hiroshima. One of those hikes took me to an overlook above Hiroshima where I found concrete foundations for an anti-aircraft battery. I had hoped that such might be visible here, but the locations provided are nebulous. Also, cement was not common in northern Thailand at that time, as evidenced by the lack of concrete roads and runways. Further, AA field units would probably have been used and these were designed to be secured on raw earth with stakes: hence there would be no evidence to be seen on the ground today. (Photo below: Handbook Japanese Military Forces (Washington: USGPO, 1944), reprint: Isby, David and Jeffrey Ethell – Baton Route: Louisiana State University Press, 1991, p 236)

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 72, 29 May 1944 (USAF archive microfilm reel A0878, p 10).[↩]

- Pantip website (offsite link-Thai Language) incorrectly uses “23 June 1944” to date the event. The back of the photo (offsite link requiring sign-in) reads: Rel for Pub [released for publication] BPR [?] 23 Jun 44 (1) WD.[↩]

- Image consists of: Google Earth Imagery data: 22 April 2010 ©2012 TeleAtlas Image ©2012 GeoEye N18°16.9′ E99°30.20 Eye alt 12.63 km Annotation with rectangular overlay by author using Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Photo and caption source: NARA Reference Number: 342-FH-3A04832-51516AC via Fold3: Lampang Airfield, Thailand (image no longer on-line. (my ref:02347 Lampang FOLD3-Lampang AF 29021505 Page 1 LPG AF photo1) ) [↩]

- Photo and caption source: NARA Reference Number: 342-FH-3A04833-51517AC via Fold3: Bombing of Lampang Airfield, Thailand (image no longer on-line).[↩]

- Photo and caption source: NARA Reference Number: 342-FH-3A04834-A51517AC via Fold3: Bombing of Lampang (image no longer on-line). [My comment: the long shadows, noticeable particularly in the third photo, indicate the attack occurred quite late in the afternoon.] [↩]

- Extract from aerial photo recorded in note 1 of 3 above; annotation added with Microsoft Publisher.[↩]

- Japanese Monograph No 177, p 15. It is not clear when this assignment in Lampang began: the battalion is listed as early as Nov 1943 as having been part of the 29th Independent Mixed Brigade, within Thailand (p 13) which became part of the [Siam] Garrison [Command] in January 1944 (p 14).[↩]

- “Record of Airfield Activity and Development”, Airfield Report No. 25, Aug 1944, p 8 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p0863).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 115, 16 Sep 1944 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A0878 p0441).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 118, 22 Sep 1944 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A0878 p0476).[↩]

- “Record of Airfield Activity and Development”, Airfield Report No. 25, Aug 1944, p 8 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p0988).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 27 (Oct 1944), facing p ii (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 pp0999-1002); my ref: \02370 Lampang\USAF archival info\440400 A8055 pp0680-8 Battleline\Battleline00-25.jpg [↩]

- ibid (excerpt).[↩][↩][↩]

- Airfield Report No. 27, Oct 1944, p 14 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p1019).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 132, 25 Oct 1944 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A0878 p0551).[↩]

- 21PRS Report Mission No. 4 MA 133, 26 Oct 1944 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A0878 p0552).[↩]

- USAAF Chrono 1944.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Jan Forsgren, Japanese aircraft in RTAF and RTN service during WWII (offsite link).[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 205. Both RTAF 1913-1983 (p 330) and RTAF WW2 (p 164) date this encounter as 17 Nov 1944; further, the RTAF histories identify RTAF aircraft as Ki‑61 Otsus (offsite link). Assignment by the IJAAF of Ki-61s to the RTAF is not confirmed by any other source.[↩]

- Young, ibid.[↩]

- Record of Airfield Development and Activity”, Airfield Report No. 28, Nov 1944, p 8 (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p1133).[↩]

- ?: CPIC, SEA, 01 ‑ 15 Dec 1944), unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8056 p0607).[↩]

- Dan Jackson email 14-Aug-22, 20:04[↩]

- The 1982 history of RTAF activities during WW2 ประวัติกองทัพอากาศไทย ในสงครามมหาเอชียบูรพา พ.ศ. ๒๔๗๔ ๑๔๗๗ (กองทัพอากาศ: กองทัพอากาศไทย, พ.ศ. ๒๕๒๕) [Royal Thai Air Force History in World War II 1941-1945 (Bangkok: Royal Thai Air Force, 1982)], p 165, had dated this action over Lampang as 17 November, and also reported four enemy fighter aircraft downed, one each in Lampang, Phayao (Google Maps link), Chiang Rai, and Shan State. Note that the digit that varies is 1 or 7 (11 or 17 November) and Thais differentiate the two primarily by “crossing” the 7; perhaps a transcriber early on inadvertently “crossed” his “1”.

In any case, the 2021 edition of the RTAF WW2 history (ประว้ติกองท้พอากาส ในสงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา ระหว่าง พ.ศ.-๒๔๘๔-๒๔๘๘ จ้ดพิมพ์เป็นที่ระลืก ในโอกาส ๘๐ ปี สดุดีวีรชนสงครามมหาเอเชียบูรพา ๘ ธ้นวาคม ๒๔๘๔ [History of the Royal Thai Air Force In the Great East Asia War Between 1941-1945 (Nakhon Ratchasima: Somboon Printing Co, Ltd, 2021), pp 249ff, date the action as 11 November which conforms to Allied records, and identifies the dead USAAF pilot as Henry Minco. No verification of downed Allied aircraft at the three other locations has been found in any other source for either 11 or 17 November.

Annotations by author using Microsoft Publisher[↩]

- The map sketch is presented and discussed at considerable length in Jan 1945 (when it was presented) in order to preserve the continuity of comparatively intense activity here.[↩]

- Summary for 14 November 1944: Brief of Principal Air Operations Reported (?: ), unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8202 p0356).[↩]

- Airfield Report No. 28, Nov 1944, unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8055 p1083).[↩]

- Photo and text from Salbani, Bengal, India (offsite link), Australian War Memorial website. “Copyright expired”.[↩]

- Summary for 27 November 1944: Brief of Principal Air Operations Reported (?:), unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8202 p0339).[↩]

- Young, ibid, p 205.[↩]

- ibid.[↩]

- Summary for 03 December 1944: Brief of Principal Air Operations Reported (?: ), unnumbered page (USAF Archive microfilm reel A8202 p0331).[↩]

- Japanese Monograph No 177: Thailand Operations Record, p 19.[↩]

- USAAF Chrono 1944[↩]

- Siam (Thailand): List of Airfields and Seaplane Stations (Washington: Office of Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence, 1945), unnumbered page (USAF Archives microfilm reel A1285 pp1221-1223). Information is dated in pages following as 31 Dec 1944.[↩]